Throughout the history of the Jewish people, entering, or maybe we should use the term arriving in, the Land of Israel and later the State of Israel, have been transformative experiences with a profound impact on the individual and in many aspects on the state of our people and our nation as a whole. When I say transformative, I mean that the moment one has entered the land something has changed and from that moment forward will have a profound impact on their lives.

Often, as they meet or interact with new arrivals and newcomers, you can hear Israeli residents use the expression, “Welcome Home.” This greeting is regardless if those who arrived have come for good, AKA made Aliyah, or have come for a few days on a tour. It is regardless if the visitor considers Israel his or her home, knows something of its history or its present circumstances or not. Many times, you can see in the eyes of those who have arrived that this welcome has ‘hit home’. They understand that as a Jew arriving in Israel it is not like arriving to any other travel destinations they have traveled to before or are planning on for their future family vacation. To any Jew it is “Home” whether they felt it before or not.

One question I tend to ask visitors upon their arrival to Ben-Gurion airport, the gateway to the land, is “what have you brought with you to Israel? Take a moment to think about it”. Usually, the rush of life doesn’t allow us the time to think of questions like this, and as we prepare for a trip we are overwhelmingly occupied by the logistics of the trip and leaving everything behind in the right manner. Usually, the first reaction I get is a packing list of everything they have in their luggage. But then I clarify my question. “It is great to know what you have physically brought with you, but that is not what I was asking, not what I meant.” I go on, “Try to think figuratively,” I say, “What kind of emotions are you bringing with you, intellectual, spiritual or even religious? What prescriptions do you have, what ‘baggage’ are you carrying, whose yearnings are fulfilled by your arrival in Israel?” I continue, “When I ask about ‘baggage’ I mean it in a positive way. Any family members, or values you ‘carry with you,’ memories and stories, this weight is ‘good weight,’ a privilege not a burden.”

We as tour-educators know that this trip through Israel will bring to the surface many of these thoughts and emotions, many times unexpectedly. We also know that this trip has the ability to put visitors back at the airport checking in for their flight home in a very different place. In a way, the trip is not a vacation, a break from life, a halt, where daily life stops, and we go for a good time to charge our batteries in our existing life so we can go home to more of the same. It is more of a pilgrimage, where the experience of your visit has a profound impact on your being, may it be intellectual, spiritual, emotional or religious. This visit has the ability to send you home differently. Some like to use the word ‘connected’ to yourself, to your people and to the Land and State of Israel. This is why the entrance and exit point to the land is so important. As a Jew, every time you arrive in the land you have already accomplished a lot, regardless of what itinerary lies in front of you.

Many travelers, visitors and Olim, new Jewish immigrants, have left us memoirs and accounts of their visits, including thoughts about their arrival and departure. Today, with social media and video cameras in the palm of each person these moments are captured in the multitudes. They are emotional and exciting to see. In a way, it is exciting like watching a video of a hearing-impaired child who has gone through a cochlear implant, who is experiencing the moment the doctor or speech therapist turns it on. The reaction of hearing for the first time is truly emotional, it is a miracle, and life changing.

As entering Israel was not always done via the Ben-Gurion airport, and not always via the air, a visit to some of the entrance points to Israel allows us to take a look at some of these transformations; from the individuals perspective in addition to its impact on the national level.

For two hundred kilometers the Southern Jordan River (SJR) meanders southbound from the Sea of Galilee, the Kinneret, to the site where it spills into the northern shore of the Dead Sea, a distance of one hundred kilometer as the crow flies. It is along this river and its banks that a number of stories in the Tanach (Bible) are acquired. It is important to recognize that the Jordan River plays a transformative role in each one of these stories. Even the stories that seem to be an individual encounter with the Jordan River have had a profound transformative effect on a much larger scale.[1]

The Jordan River is mentioned in the Bible 176 times, it is not a holy site on its own, yet the events that have occurred along it have given it a significant place in the Jewish as well as the Christian traditions and others.[2] Can we identify the exact site of these events, most probably not. Can we visit a point at the river, in order to understand the landscape, the framework of the stories and better understand the transformation- I believe we can.

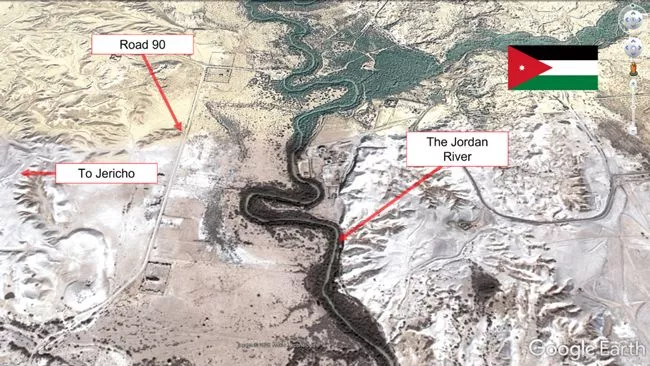

One of these sites is just east of the city of Jericho, known today as Quasr El Yahud. To arrive at the site, we must turn off route 90, the eastern north-south road of Israel, and drive east towards the Jordan River. We must cross the security barrier (fence) and descend down to the Jordan River. We will always be within the borders of the State of Israel. The political border is in the middle of the river, and when we arrive at the river we will see it is marked by a line of yellow floating buoys. A closer look and you can spot the Jordanian flag and soldiers on the eastern banks. The security barrier (fence) has been put in its place due to the terrain, in order to allow a safe zone and strategic depth for the IDF (Israeli Defense Forces) patrol. Due to the stability along this border, and the significance of the site, access to the site has been arranged.

The site has been recognized as the area of many significant historical events, amongst them the crossing of the children of Israel led by Joshua Ben-Nun into the promised land, following the exodus from Egypt and forty years in the desert, the site of where Elijah the prophet rose to heaven and the baptismal site of Jesus. On both banks of the river, there are Christian Monasteries dedicated to these stories.

Following an intense and dramatic family drama, and a famine in the Land of Canaan, the children of Jacob make their way to Egypt. A large family in search of substance to take care of their

own during times of struggle. An extended family in search of survival. By the

time they make this mass departure, this Exodus out of Egypt, these families

will become one large family bound together by slavery, set free by God through

the leader of the people, Moses. By this time, they are not just a very large tribal

clan, but one people, different from those who they dwelled amongst, with a

shared history, experience and values. These ‘People’ will gather on the

foothills of Mt. Sinai where God, the creator of the universe, will reveal

himself before them, and a covenant will be born between them – You will be my

people, and I will be your God.

Forty years later, after the death of the Desert Generation, and a change in Leadership from Moses to Joshua, these People with their Covenant left the plains of Moav and entered the land

of Israel. The crossing of the Jordan River, was a miraculous moment described

in the book of Joshua:

“When the people set out from their encampment to cross the Jordan, the priests bearing the Ark of the Covenant were at the head of the People. Now the Jordan keeps flowing over its

entire bed throughout the harvest season. But as soon as the bearers of the Ark

reached the Jordan, and the feet of the priests bearing the Ark dipped into the

water its edge, the waters coming down from upstream piled up in a single heap

a great way off, at Adam, the town next to Zarethan; and those flowing away

downstream to the Sea of the Arabah (the Dead Sea) ran out completely. So, the

people crossed near Jericho. The priests who bore the Ark of the Lord’s

Covenant stood on dry land exactly in the middle of the Jordan, while all

Israel crossed over on dry land, until the entire nation had finished crossing

the Jordan”[3]

The crossing of the Jordan River encompasses in it one of the most important transformations the Jewish People have endured. A People with a Covenant with God now have their own Land. The crossing of the Jordan is the first deliverance and fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham,

Isaac and Jacob.[4]

This transformation to a people with a land brings with it a responsibility to the land. This can be seen with the first deeds that take place on the land – the circumcision of the Children of Israel at Gibeath-Haaraloth,[5] the offering of the Passover sacrifice,[6] and the battle for the city of Jericho.[7] In addition, the day after the Passover sacrifice, the children of Israel started to eat from the produce of the Land, the manna, the food provided to them by God during their time in the desert ceased.[8] No more will they be solely dependent on God, rather they must partner with him, work hard to cultivate, nourish and nurture the land and produce from it sustenance.

The transformation will change the course of the Jewish People forever. A people that was born in Egypt, outside their promised land to be, are now attached to a land indefinitely. In this land they must live with a covenant with God, a covenant that demands partnership and brings good into the world, for if not, “the land spew you out for defiling it, as it spewed out the nations that came before you”[9]. For the next 3,000 years the Jewish people will refer to the Land of Israel as their Homeland whether they are dwelling on the land, or in the diaspora. The crossing of the Jordan River changed the Jewish people forever.

For centuries one of the main entrances into the land of Israel was through the Port of Jaffa.[10] On the Mediterranean coast, between Alexandria in the south and Tyre in the north, Jaffa served as an access into the mainland and to Jerusalem. With the decline of the Ottoman Empire and transition into the new modern world – steam boats, trains and new ways of travel, Jaffa became a gateway for many travelers who sought a way to arrive in Palestine through academic and research expeditions, religious pilgrimages as well as leisure travel. For them the Jaffa port was the gateway to the land, the first encounter with this much desired land.

From the middle of the 19th century, among these groups were Jews who were seeking to change personal and national statutes by arriving in Israel to ‘Livnot U’Lehibanot’ build and to be built. From here the new Zionists will head out to create a new society, a new Jew in their old land. From Jaffa they set out to join the Old Yhishuv in Jerusalem, to establish the first Moshavot, such as Petach Tikva, Rishon LeZion, Rehovot, Zichron Yaakov and others, mainly attributed to the members of the First Aliyah. Later on, the Kibbutzim and the city of Tel Aviv both attributed to the period and members of the second Zionist Aliyah. Imports and Exports of goods will come through Jaffa as the famous Jaffa Oranges. This will continue until the 1936 riots, then the Jews will build a small port in Tel Aviv next to the Yarkon river, and the deep port in Haifa and later Ashdod will take its place.

On the boat, the Olim, the new immigrants, would get their first glimpse of Jaffa. From the sea, the city and the land look magical. A Millennia old collective yearning for return to the land is on the horizon. Tikvah, a hope for a better future, personal and collective, is waiting on the docks. The dream is finally becoming a reality. And yet a dream is one thing and reality another. In Jaffa reality would hit. The arrival at our promised land, and the hardship of building a new life in a land that was neglected and dilapidated. Upon the soil of the Land of Israel, the personal and national redemption is stricken by the harsh and unforgiving reality.

S.Y. Agnon, Israel Nobel Prize Laurate for literature, in his monumental novel Only Yesterday describes the period of the second Aliyah. In the description his protagonist Isaac Kumer Agon shares his personal experiences and feelings. Agnon describes beautifully the spiritual and emotional feelings of finally arriving to the land, after 2,000 years of exile, and the harsh reality that comes with it.

“Isaac stood there on the soil of the Land of Israel he had yearned to see all the days of his life. Beneath his feet are the rocks of the Land of Israel and above his head blazes the sun of the Land of Israel and the houses of Jaffa rise up from the sea like regiments of wind, like clouds of splendor, and the sea recoils and comes back to the city and does not swallow the city nor does the city drink up the sea. An hour or two ago, he was drinking the air of other lands, and now he is drinking the air of the Land of Israel. No sooner had he collected his thoughts than the porters were standing around him and demanding money from him. He took out his purse and gave them. They demanded more. He gave them. They demanded more. Finally, they wanted baksheesh.”[11]

The clash between the dream and reality is immense. The euphoric expectations shatter in the face of the grim and difficult reality. And yet, each and every one that came through Jaffa was transformed – they are home. They arrived in a Land where they will build together a personal and collective future. A new Jew will be born.

During the end of the 1960’s and the beginning of the 1970’s an Israeli group of artists known as the Lul group put out a series of shows that included songs, monologues and sitcoms that shed light on multiple issues regarding the Israeli society. One of these sketch-comedy scenes is known as the ‘HaOlim HaChadashi,’’ the new immigrants.[12] The scene takes place at the Jaffa port, as waves of new Jewish immigration arrive in pairs, played by the famous Arik Einstein and Uri Zohar. First came the early Russian Aliyah in the beginning of the 1880’s, followed by the Polish, Yemenite, German, Moroccan and the Georgian-Russian Aliyah. Each arrival gives us a humorous glimpse into their first experiences with the land. Each group with its unique cultural and spiritual background and with their hopes for a new future.

But this is not all, in a brilliant and humorous form, this sitcom allows us to engage in another issue – the relationship between the Vatikim – the old-comers, and the Chadashim- the newcomers. The skit does not give us an idea of how long the wait between each wave was, which makes it all the more interesting. Once a new wave arrived, the previous wave already saw itself as Vatikim- old-comers and allowed themselves to commit and share their thoughts regarding the newcomers, their ways and traditions and what can be expected from them. By the end, each wave is shouting out about what they had endured since they came, what they have built and contributed to the society, to the extent of accusing the newcomers of, “how dare you just come now, just like this, what you arrived to, we built, we sacrificed for!”

In a way, this sitcom shows the transition of the Jewish Zionist Olim arriving in Jaffa. On the one hand the place they are coming from, the emotions and yearnings to arrive to Israel, the reality of Israel, and the options of transitioning and becoming a Vatik- Old-comer, integrated and contributing to society.

Looking north from Jaffa one can see today the skyline of the city of Tel Aviv. In a way, from the founding of the city, it has been one of the Zionist symbols of building a country for a new Jewish society.[13] The Hebrew City, The Gymnasium, Ivrit Herzliya- as the educational institution to raise this new Jew, architecture, banking, cultural institutes and more have all served the purpose of creating this new state.

Today on the top of the hill, the highest point in Old Jaffa, known as Gan HaPisga, stands the ‘Gate of Faith’- a large sculpture created by Israeli Master-Sculptors Daniel Kafri. The sculpture stands at the top of the hill, four meters tall and four meters wide. From this vantage point you can see the city of Jaffa to the east, the Mediterranean Sea and the entrance to the port to the west, and the city of Tel Aviv to the north with its magnificent and impressive shore and skyline. The sculpture designed as a gate, resembles the gate built by Ramesses the second, those remains were found in an archaeological excavation in Jaffa, and a replica of it stands not far down the hill.

The Gate is sculpted as the entrance gate to the land. On the one doorpost (pillar holding up the gate) is a depiction of the biblical story of the binding of Isaac. Abraham is holding up his son Isaac, and by his side lays the Ram – the symbol of the promise made to Abraham, “I will bestow My blessing upon you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore; and your descendants shall seize the gates of their foes.”[14] The second doorpost is a depiction of the biblical story of Jacob’s ladder. Jacob is laying on a stone and above him are two angels, one going up and one coming down. This is a symbol of the promise made to him, “Your descendants shall be as the dust of the earth; you shall spread out to the west and to the east, to the north and to the south. All the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you and your descendants.”[15]

Above these two pillars spans a four-meter-long lintel carved and sculpted on both sides. It depicts the biblical sense of the capturing of the city of Jericho by the children of Israel led by Josiah Ben-Nun as they enter the Land of Canaan. On it we can see the priests as they carry the Ark of the Covenant around the city walls for seven days before they collapse. This scene represents the beginning of the realization and fulfillment of the promise to our founding fathers. The first deliverance of the land to our people.

Standing on the south side of the sculpture looking north through it one can see the city of Tel Aviv. In a way, the Jordan River and the conquering of Jericho were the gateway to the first deliverance, just as Jaffa served as the modern gateway for the Zionist deliverance of the land, that is represented in the modern Hebrew city – Tel Aviv.

The Zionist dream of building a state became a greater challenge as the tension between the Jews and Arabs escalated in the 1930’s and 1940’s of the 20th century, under the British Mandate. Quotas were imposed on the number of Jews allowed to annually enter the land. This was known as “The White Papers.” A Jewish underground organization given the name “Aliya Bet” or “Ha’apalah” operated secretly in order to bring Jewish immigrants to Israel. These illegal clandestine immigrants were known as Ma’apilim. This became more urgent after WWII, as Jewish survivors were seeking a new home. The British reaction to Aliya Bet after WWII was impressive and effective. A Navy blockade was imposed on the coast of Palestine. Only 12 Aliya Bet vessels managed to run this blockade, with just 2,108 ma’apilim on board. The rest of the ma’apilim – 66,160 people, were caught and detained by the British. The vast majority of them were detained in special detention camps in Cyprus. Other detention camps included the Atlit detention camp south of Haifa, and 2 camps near Hamburg Germany. The British gradually released the ma’apilim as part of their allocated monthly quota of certificates (1,500 per month).

The Atlit camp is located on the foothills of Mt. Carmel, on the coast just south of the city of Haifa. The camp was intended to house the ma’apilim until they were released at the expense of the British immigration quota. A sanitizing hut was created where the ma’apilim were sprayed with DDT to prevent the transmission of diseases. 100 wooden barracks which housed the ma’apilim under strict separation between the boys and the girls during the nighttime. The establishment set up clinic barracks, kitchens and dining rooms.

The camp was surrounded by fences and guard watch towers. For the ma’apilim that arrived from Europe, this brought up memories of the camps they fled from. Let’s be clear, even though the outside might resemble the camps in Europe, by no means were they treated like this.

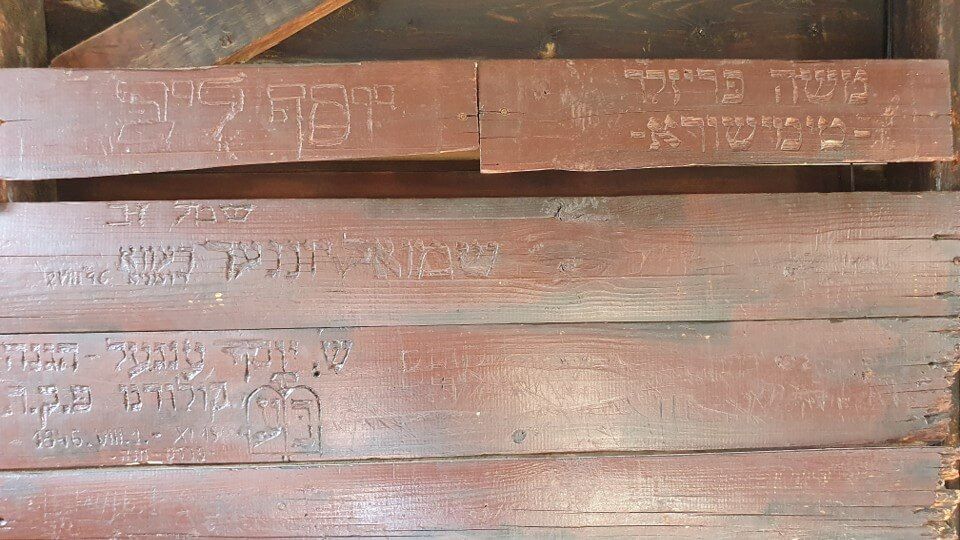

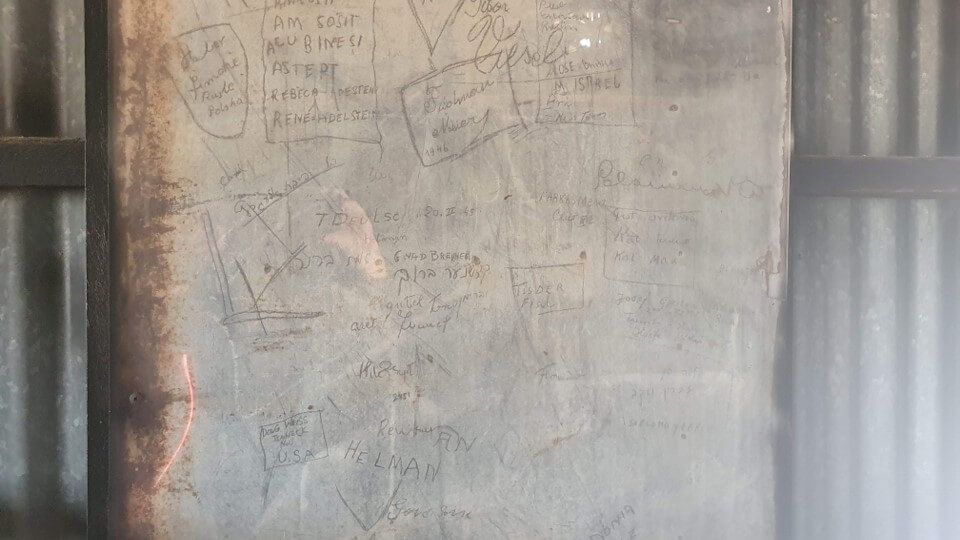

Upon arrival at the camp, inmates would carve on the walls of the barracks and in the disinfection barracks their names, their origins, the name of the ship they arrived on, the youth movement they belonged to, and any other significant information regarding themselves. It was their hope, that just as they arrived in Israel, maybe another family member, neighbor, or acquaintance also survived and will come through the same barrack and will learn that they are alive and will look for them once they get out of the camp. Maybe, just maybe, there would be a chance to find a remnant of the past.

When word got out in the Yesuv, that a ship was caught and new ma’apilim were detained in Atlit, Jews from all over the country would flee to the camp, stand outside the fences and call out names of family they had in Europe before the war, and their origins, hoping maybe someone survived and made it to the camp.

Holocaust survivor Moshe Avital writes about his unification with his brother:

The next day, while I was in the barrack someone came in and asked who was Moshe Doft-Lipshcitz. I said I was. He said my brother was waiting for me at the gate. The British did not allow visits, but one could stand at the gate. I rushed to the gate. I recognized my brother right away because he was 18 years old when he left home. He had not changed much and he had also sent pictures home from Palestine. My brother did not recognize me because I had changed a lot. When he left home I was only 8 years old and now I was 16. I looked very different. Also, it was hard for him to believe that Moshe’leh, the child that he had left, could have survived the Holocaust. My brother asked me all kinds of questions about the family to make sure I was really his brother. He asked me the names of our fathers and mother, the names of our brothers and sisters, from what town I came, what our father did. Only after this thorough quiz did he come to the conclusion that I was really his youngest brother.

Both of us cried…I was able to enter the Land of Israel, a great dream fulfilled.[16]

Another group of ma’apilim that was caught by the British and detained at Atlit are known as The Buchenwald Children. 152 young survivors who made their way to the Land of Israel on a ship by the name of Mataroa. On July 15, 1945 they arrived in Haifa and were brought to the Atlit camp. One of these children, known as Lulik, arrived with his older brother Naftali. Eventually they were released, and this little Lulik grew up to become Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, the Chief Rabbi of Israel and the Chairman of Yad Vashem.

Rabbi Lau in his autobiographical book describes this seance, and gives us his account of uniting with his half-brother:

We stayed in Atlit for two weeks, during which time I could barely close my eyes at night. Like jackals howling in the wilderness, people stood for long hours outside the barbed wire fence surrounding the camp, issuing heart wrenching cries that still echo inside me. At night, when all was silent, those cries had particular impact. We would hear a shout “Greenberg, Drohovitz!- that meant someone was looking for a person named Greenberg from the town of Drohovitz. Or “Goldberd, Lodz!” the noise continued from many long days and nights. People left their work, walking or hitching rides if they lived far away, in order to search for surviving relatives or to glean any scrap of information about their dear ones. We, the prisoners in the camp, were a bridge that connected “here” to “there.”

Someone was also looking for Naphtali and me. As soon as we entered the cabin at Atlit, a local representative approached Naphtali and introduced himself as Mr. Kisman, a member of Kfar Etzion, a religious kibbutz located in Gush Etzion (The Etzion block), between Jerusalem and Hebron. He was one of many representatives of agricultural settlements at Atlit. Mr. Kisman gave Naphtali greetings from “your brother Shiko.” At first Naphtali did not understand whom he was talking about. He tried to explain to the man that there must be some mistake, and that message must be meant from someone else. But Mr. Kisman insisted, and added that Shiko was on his way to Atlit.

Finally, Naphtali realized that he was referring to our half-brother, Yehoshua (Joshua) Yosef Lau-Hager, nicknamed Shiko, Naphtali had last seen him twelve years previously, when Shkilo went to celebrate his bar mitzvah at the Polish home of his grandfather, Yisrael Hager, Rebbe of the Nizhnitz Chassidic sect….

Among the crowds pounding on the gates of the barbed wire fence in their desperate attempts to glean information, I heard Naphtali and another man shouting to each other: “Tulek- Shiko!” “Shiko-Tulek!” I heard the other man’s voice among the hoarse cacophony of shouts coming from the throngs of strangers, Then I saw the man behind the voice: he wore khaki pants, and short -sleeved khaki shirt, and open-toed sandals without socks. At twenty-six, his mane of hair had already begun to turn white, and his forelock peeked out from under his cap.

As I was studying him, Naphtali turned to me and said, “Lulek, meet your brother.” I did not know how to react. Shiko had seen me at our home in Piotrkow during the first two years of my life, when he came to visit from the holidays. But to me, he was a complete stranger. He stretched his hand over the fence, trying to shake my hand but reaching only my fingertips.

Although in Atlit I was happy about gaining a brother, the rest of my experience there was filled with mixed emotions.[17]

For the ma’apilim survivors that arrived in Israel after the war, arriving in Israel, and to an extent arriving at the Atlit Detention Camp, became an option to search for family, reconnect with lost loved ones and rebuild a new life. This arrival was transformative, as it moved them from survival mode to rebirth mode.

The Atlit camp became the symbol of Britain’s struggle against immigration to Palestine, and therefore on October 5, 1945, a group of Palmach fighters broke into the camp and relisted 208 illegal immigrants.

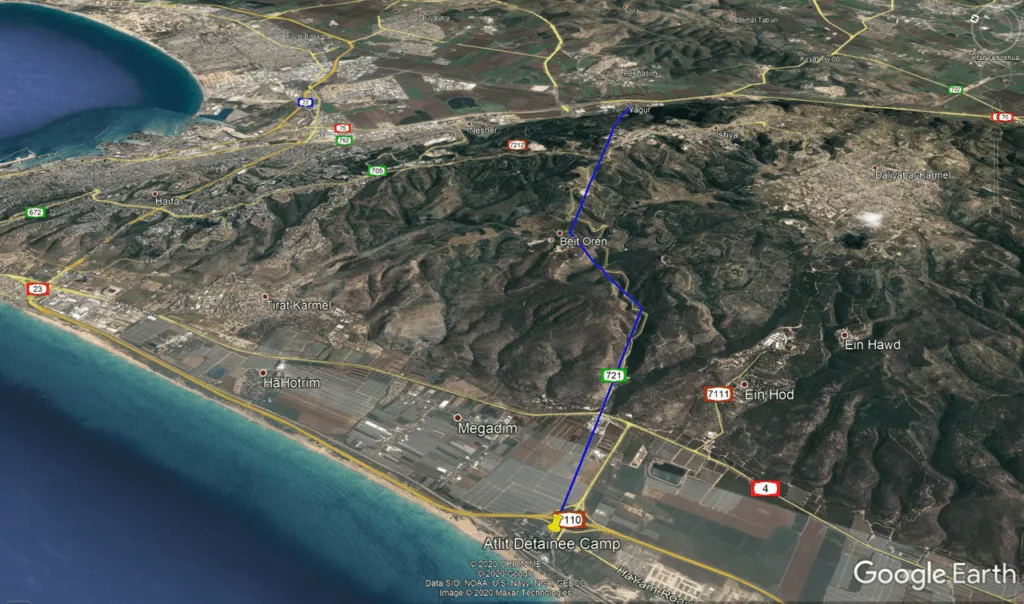

On October 5, 1945 the British planned to deport 300 clandestine Jewish immigrants who were caught crossing the Syrian border into Israel near Kfar Geladi. In response the Palmach decided to launch an operation to break out Jewish detainees from the Atlit Detention Camp. The operation was led by Nahum Sarig and Yitzhak Rabin. 2 days before, fighters under disguise as Hebrew teachers were sent into the camp, and together with Jewish Policeman in the British police, sabotaged the camps guards’ guns. The plan was to, under the cover of darkness, to cross the fields on the coastal plains outside the camp, climb Mt. Carmel via Nahal Oren, and descend down the other side to Kibbutz Yagur. From there they would disperse the ma’apilim among the Jewish settlements in the area.

The walk took longer than expected and by the time the Palmach members and the ma’apilim arrived at the Kibbutz the British police had discovered the operation and surrounded the Kibbutz. Over 1,000 residents from Haifa and the surrounding communities filled the Kibbutz, blending in with the ma’apilim, and eventually the British gave in and didn’t enter the Kibbutz. The ma’apilim were hidden in the homes of the Yagur Kibbutz members, and later dispersed around the country.

Yoram Taharlev, an 8-year-old boy growing up in Kibbutz Yagur experienced this first hand. As a young boy, he remembers giving up his bed for ma’apilim who stayed for about one month until they moved to new places around the country. Many years letter he will write the song “Tzel Umei Be’er” – Shade and a Well of Water, expressing his appreciation and admiration towards the Kibbutz, while describing the Kabbalat Panim, welcome and hospitality they extended towards the newly released ma’apilim.

The song opens with a wonderful description of the Carmel Mountains, and moves into the chorus.

“The hungry one will find a slice of bread

The tired will find shade and water from the well

The one that his house is falling down will come in quietly

And will be able to stay forever”

The last stanza of the song,

“This is the house we built this is the grove we planted

This is the path and the well

Whoever comes here is a brother

And will sit down to the table with us

The gate will never close again”

Yoram Taharlev expresses the transformation these ma’apilim go through as they arrive in Israel after WWII. A transformation of hope, of rebuilding a home. What the Land of Israel and the Zionist Dream will offer these new Olim is a family and a home for those who did not have one, or lost it due to the war.

3 years later, on the 13th of May 1948, David Ben Gurion, in the city of Tel Aviv, will stand up and Declare the Independence of the State of Israel. In the declaration it states: “THE STATE OF ISRAEL will be open for Jewish immigration and for the Ingathering of the

Exiles”.[18] In order to anchor this statement into the new born state, in 1950 the Law of

Return was legislated in the Knesset, stating “Every Jew has the right to come

to this country as an oleh”.[19] And in fact, to this day many Jews from around the world have exercised their right by immigrating to Israel and becoming respected citizens of the state of Israel on the basis of being Jewish. The contribution of Olim has been instrumental to the building of the state. But, what lies before us is far more reaching then the State of Israel, or even the Olam themselves.

What lays here is the determination of a two millennia old condition known as ‘The Jewish Refugees.’ On May 14th, 1948, David Ben-Gurion brought this to an end. The idea that any Jew, anywhere in the world, in any condition (whether in stress or by choice) always has one place she or he can come to, and make it her or his home, has changed the personal status of every single Jew in the world. Whether or not a Jew living outside of the State of Israel decides to move to Israel or not is irrelevant. Whether she or he is engaged in a relationship with the State of Israel is irrelevant. Ever since 1948 Jews have a safe place, a home. This status is structured into the DNA of every Jew today. For two millennia this was a dream, 75 years ago it was achieved through effort and battle. For 5 decades, and to an extent for the generation that witnessed it until today- it is considered a miracle. Today, for many it is a given, maybe even taken for granted. Yet nevertheless a status every Jew carries wherever they may be.

Following the Declaration of the State of Israel and the conclusion of the War of Independence with the signing of cease-fire agreements in Rhodes, Jews from around the world rushed to Israel. Shoah Survivors now have a legal way to leave Europe. Jews from North Africa and other Muslim countries in the region have been under growing threat

and harassment will find their way to Israel for refuge. Absorbing this new Olim into the young country will be one of the most significant challenges of the first decade of the state. Within ten years, the country will absorb over one million new Olim, mostly Jews in need coming from stressed countries. During this period the Jewish population in the country will more than double itself.

This mass immigration to the State of Israel will bring along with it a transformative experience for the Jewish People. From a people with many diasporas, The State of Israel will become a people of many diasporas in a homeland. These waves of immigration, Aliyot, will not stop to this day, adding to the diverse population more and more diversity. True, it will still take over 60 years for the state of Israel to become the largest Jewish community and Jewish center in the world. Vatikim, old comers, and Tzbarim- Israeli born Jews, and Olim – will always exist in our society.

How did and how do we handle this ongoing absorption? Some would argue that the Ashkenazi leadership of the state imposed a system of melting pot. “Israelization’ – everyone must step up and work to become the true and contributing Israeli- as they pictured it. In some sense, this might have been needed in order to maintain the state. Yet a price was paid. Today, we are much more aligned with celebrating our differences, learning other backgrounds and practices, blending traditions. Many of the young families today are made up of a mixture of backgrounds.

Yet, we can’t disregard the fact that during the first decade of the State of Israel for the first time not only did Jews from many backgrounds and traditions meet Jews from other backgrounds with different traditions, but that their fabric of life has been woven together, and there is a need to build the country and a shared society together.

Take for example cities like Yeruham in the south of Israel, founded in 1951 as a Ma’abara, immigrant and refugee absorption camp, and one of Israel’s first development towns, created to house the new Olim and settle frontier areas of the early days of the state. The first influx of Olim came from Romania, many of them Shoah survivors, followed by Olim from North Africa, in particular Morocco, Persia, India and elsewhere.

This ‘Ingathering of the Exiles’ from four corners of the earth to the newly born state of Israel, and the mix or sometimes clash of traditions and societies took place all over Israel.

Another example would be the Kiryah HaYovel neighborhood in Jerusalem. Rav Haim Sabbato, who grew up in this neighborhood, in his book From the Four Winds, shares with us the amazing relationship developed between the storyteller – a young immigrant boy from Egypt, and Moshe Farkash, a Shoah survivor from Hungary. From the 1950’s these two groups of Jews were housed together in Beit Mazmil, in the Kiryat HaYovel neighborhood in southwestern Jerusalem. The story is based on the writer’s personal experiences and includes many autobiographical details.

Sabbato describes the journey to Israel of these two groups together.

“On the ship which brought us from Genoa, Italy to the land of Israel, all the immigrants from Egypt, who had been expelled after the Sinai campaign, travelled together with immigrants from Hungary. For an entire week the little swaying ship sailed across the Mediterranean Sea from Italy to the land of Israel. They told us that this was the smallest ship there was in the land of Israel, and that during the mandate it had been used as a blockade runner. Even then we saw that the Jews from Hungary were silent and worried all the time, but we did not know why. Over the course of the day they hardly ever emerged from their berths. We only saw them in the mess hall at meal times and during the joint prayer sessions. The liturgy was the same liturgy but we could not understand the accent…

In contrast to the Hungarians, who remained holed up in their berths, the Egyptians loved to rove about in groups, to climb up to the deck, to make conversation, and to laugh. Such was the way of the Jews of Egypt; even in times of distress they loved to chat and joke around. Even the seasickness was a cause for laughter among the Egyptians…

Emissaries from the Jewish Agency distributed apples and Jaffa oranges throughout the ship. The oranges were supposed to give us a taste of the land of Israel, while the apples had been purchased in Italy. They said that one of the Hungarian Jews on our ship had purchased forty crates of apples in Genoa and sold them in Haifa. He lived off of the proceeds for the next three months. A Jew enveloped in a beard approached Father. Father was delighted to start a conversation with him. Father knew Hebrew from Scripture and from the liturgy in the siddur, but the accent of the Hungarian Jew was totally different, to the point that Father was unsure whether or not he was actually speaking Hebrew. After a few attempts and hand gestures, Father burst out laughing. The Jew had asked if we would switch with them: they would take our oranges and give us their share of the apples. Father explained the logic behind the exchange: in Egypt the only people who ever had apples were the wealthy or the sick; but in Hungary, apples were available in abundance while citrus fruits were nowhere to be found. “Take all of these and all of those,” Father said.

They housed us all together in Beit Mazmil.”

The establishment of the State of Israel and the mass immigration that followed brought with it a transformative experience for the Jewish People. From a people with many diasporas, The State of Israel will become a people of many diasporas in a homeland. This newly shared society will transform the Jewish people living in Israel. A multifaceted and multicultural Jewish community exists all around Israel. Today, around Israel there are many pockets of ‘Edot’ – Jewish Ethnic Backgrounds, where original traditions are safeguarded from change and strictly observed. And yet, three generations later, families in Israel are made up of multiple backgrounds and traditions. A new nuclear family today can be made up of 4 different and diverse backgrounds, each contributing to the fabric of this new Israeli family. Multiple traditions are taught and celebrated through the Israeli school system, and synagogues and places of culture are practicing multiple traditions simultaneously.

Time and again the state of Israel will be transformed by these waves of immigration. In addition to the personal transformation obtained by each Oleh, and the transformative process that comes with an ongoing evolving society, the oncoming waves of Aliyot will create challenges that strike core issues regarding the identity of the State of Israel.

[1] A list of the biblical and rabbinic stories include: Genesis 32, 10-33 – Jacob returning to the Land of Israel, wrestles with the Angel of God, and receives his name Israel; Joshua 3-4 – the Children of Israel cross into the land of Israel after 40 years in the desert; 2 Samuel 17, 22- 20, 2 – King David running from his son Absalom; 2 Kings 2, 1-15 – Elijah was taken up to heaven; 2 Kings 5, 8-15 – Naaman the leper immerse himself in the Jordan river; Matthew 3 13-17, Mark 1, 9-12 – The Baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River; B. Talmud Baba Metzia 80A – Rabbi Yohanan and Reish Lakish meet on the Jordan River.

[2] All transformative events along the Jordan river that appear in the bible are attached to the act of crossing the river. From the East bank to the West, or from the West of the East, and in some cases back and forth. Understanding the geography of each story is necessary to unpacking the story and understanding its deep transformative effect.

[3] Joshua 3, 14-17.

[4] The promise of the Land: Genesis 15 18-21, Genesis 28 13-16.

[5] Joshua 5, 4-9.

[6] Joshua 5, 10.

[7] Joshua 6.

[8] Joshua 5, 11-12.

[9] Leviticus 18, 28.

[10] Those who came through Jaffa

[11] S.Y. Agnon, Only Yesterday, Book 1 Chapter 1, Pp 39-40. Translated from the Hebrew by Barbara Harshav.

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MBNWHTipwEA&t=196s – with English subtitles.

[13] Other places/ forms of creating the new Jew- Kibbutzim, the defense organizations, a vibrant economy, and more.

[14] Genesis 22, 17.

[15] Genesis 28, 14.

[16] Not to Forget Impossible to Forgive: Poignant Reflections on the Holocaust, by Moshe Avital, PP 174-179

[17] Chief Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, Out of the Depths: The Story of a Child of Buchenwald Who Returned Home at Last, translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Setbon and Shira Leibowitz Schmidt, New York 2011. Chapter 7, PP 96-

[18] The Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel – on the webpage of the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs here

[19] The Law of Return on the Knesset website here