This is a story about a road, or rather a strip of one hundred meters along a very busy market street in the old city of Jerusalem, where small miracles take place every day. Yep, small miracles that we can’t see. Small miracles take place everywhere around us and all over the world, and most of the time we dismiss them as life. In Jerusalem we expect miracles, and many times we claim situations to be miracles, but the small ones, heavenly miracles upon Earth, that accrue again and again – we tend to see them just as life. They are colorful, yet regular – and as so, they happen, and we move on with life.

This is also a story about people. It is about the many people who live along this street, those who use it daily to get from one place to another or to shop at the many stalls on either side of the street. It is also about the people who have traveled from far to visit and to be inspired by the sights along the street. It is a story about the many people who participate in a miracle along this street.

One of my favorite things to do in the old city of Jerusalem is to take a break on a corner of this street and watch, and when I say watch, I mean people-watch. I sit there at one of the restaurants with a cup of black-coffee, mud coffee, and my eyes wander the street, following individuals and groups passing by.

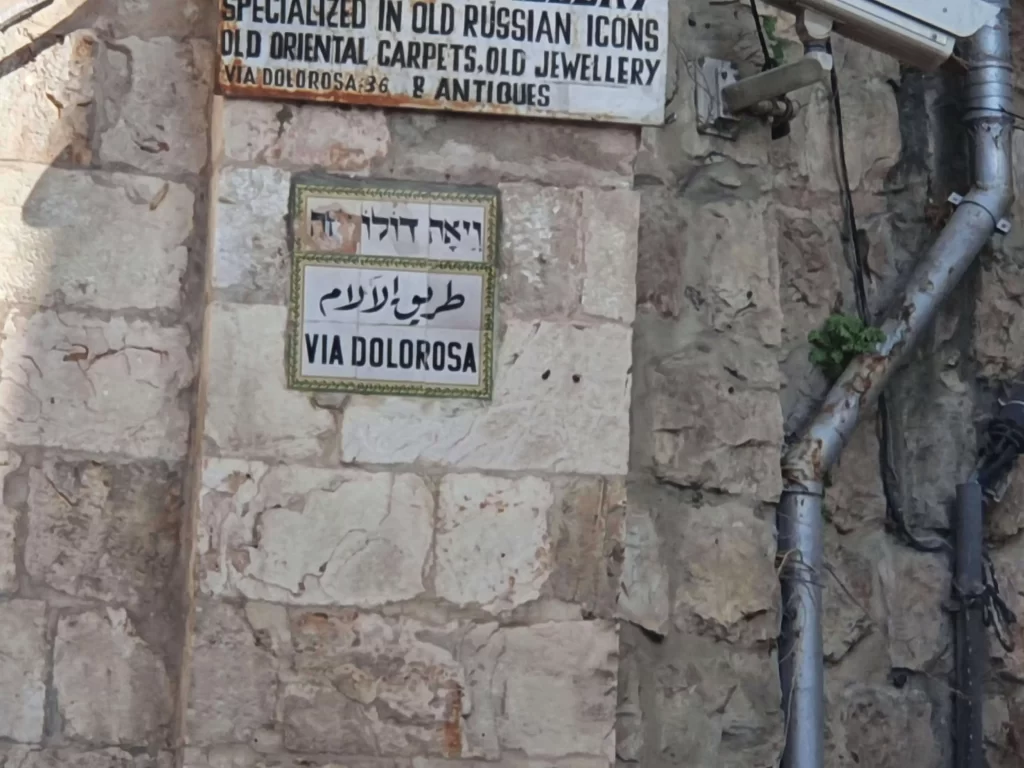

Let’s put the pin on the map. We are in the Muslim quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. We are on the road known in Arabic as Al Wad and in Hebrew as Hagaii street. The language we use has political implications, but in both languages, it means the valley street, and it runs from north to south along the main valley of the Old City[1], separating Temple Mount to the East, from the Western Hills of the Old City, today’s Christian and Jewish quarters. It enters the Old City in the north at the Damascus Gate, and runs south through the Muslim quarter, the Western Wall Plaza, out the Dung Gate, through the Silwan – City of David neighborhood and excavations, again another political observation, until it finally reaches the Kidron Valley. The intersection at which I sit is with Via Dolorosa Street, which runs from Lions Gate on the East. The streets overlap running south for approximately 100 meters, and then the Via Dolorosa turns right, west, and ascends to the western parts of the Old City, ending up in the heart of the Christian quarter at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

I sit on the western side of the street. This allows me to look up and down with a panoramic view of the intersection. Looking north straight up towards the Damascus Gate, the street is lined with stores and stalls on both sides, and one can see a house that hangs over the street held up by a big arch. It is very noticeable due to the big Menorah that is situated on its roof and the Israeli flags that adorn its walls. Purchased by the Vitenburg family in 1885, it is better known as the home of former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who bought the house in 1987 in order to force the then-government to provide protection for Jewish citizens living in that area of the city.

On the northeastern corner of the intersection, people enter and exit a beautiful complex through wooden doors. This is the Austrian Hospice, built in the 1860’s, and it hosted, among others, Emperor Franz Joseph the First during his trip to the inauguration of the Suez Canal, and pilgrimage to the Holy Land. The Austrian Hospice is an island of Europe in the middle of this very Levantine city. It offers a great view of the city from its roof and is a place of refuge and rest in the form of classic apple strudel and coffee in its beautiful garden cafe.

Just across from the Austrian Hospice is the site of the 3rd and 4th stations along the Christian pilgrimage route of the Via Dolorosa, the Way of Suffering. These stations traditionally mark sites of incidents that befell Jesus Christ on his last journey, to the site of his crucifixion and ultimately burial and resurrection. These sites have been marked since the Middle Ages, and over time their ownership has been claimed by the different Christian denominations who have built chapels, churches and various other markers on these sites. Believers and pilgrims from all over the world follow these stations, walking in the footsteps of Jesus, and often stop to reflect and pray at the stations. Stations three and four were built and are run by the Armenian Catholic Church and commemorate Jesus’ first fall and first encounter with his mother Mary. In front of the stations behind low metal portable fences stand young men and women in Border Patrol uniform, a testament to the complex political environment and the security tension that lies in these streets.

With a glimpse down the street, to the south, I can see the continuation of the market on both sides of the street, and in the near distance, the pilgrims turning off the street heading west up the hill.

On any given average day these streets are full of a colorful and diverse array of people, making the people- watching exciting. Local Muslims are doing their shopping. An educated glimpse glance will reveal multi-generational Muslim families, often with a matriarch dressed in traditional attire that includes a long dress and Hijab head cover, alongside her daughter in skinny jeans and Hijab, and her granddaughter dressed in the most recent brands and trends, not putting to shame any teenager in the city or around the western world. Jewish locals use this street too. Some live in the area and some are on their way to the Jewish sites of the old city. Time and again we can spot ultra-orthodox Jews cutting through the crowd in their traditional black and white attire on their way to pray at the Western Wall or to learn at one of the many Yeshivot, study halls, in the old city. Tourists stand around their guides as they point out places of interest, listening to explanations in many languages regarding the sites, the history, and current events. Some are taking pictures with cameras or their cell phones, and others are offering prayers and benedictions.

As I mentioned, this site is a site of small miracles. One of them takes place every Friday. It is not a miracle that takes place once, or not even in one moment. It is not something that changes its surroundings dramatically. Nevertheless, it is a miracle.

It begins during the first few hours of every Friday. For the Muslim population of Jerusalem, Friday is Al Jumh’ah day: the day of gathering the people to the big mosques for prayer and listening to the preaching of the Imam. Muslims have local mosques in their neighborhoods, yet on Friday they go to the big mosque, and in Jerusalem this means Haram al-Sharif, Temple Mount. On the western side of Temple Mount there are many entrances that can be accessed via Al Wad Street, the street I sit on, sipping coffee and people-watching. Many of the Muslim neighborhoods in Jerusalem outside of the old city are to the north and east of the walls, making the Damascus Gate a convenient entrance point. So, every Friday, and especially on special religious days, such as during the month of Ramadan, hundreds, thousands, and sometimes tens of thousands of Muslims poor into the city walking straight through our intersection. They will come for their prayers, but will not miss the opportunity before or after to shop in one of the many stores for their festive meals. By the afternoon the crowds will clear off and the street will go back to normal, for just a short time.

That same day, in the very same place, in the late afternoon, around three or four o’clock, groups of Christians will begin their journey on the Via Dolorosa. As with the Muslims, throughout the country and in Jerusalem there are many churches and sites for all denominations to offer prayer, and to celebrate Mass or Communion. Yet, as we have already mentioned, the opportunity to walk in the footsteps of Jesus to his crucifixion is parallel to non-other. All the more so when it is on Friday, the day of the crucifixion (Good Friday). Groups of believers barring a wooden cross on their shoulders walk the stations led by a priest or member of the clergy. They stop at each station to offer a prayer and then move on to the next. The groups are a mixture of members of the church, clergy of various denominations. They can be distinguished by their garbs, language of liturgy, and sacred instruments. They overlap with the same street as the Muslims did just a couple of hours prior. I watch them as they pass stations three and four, continue to the next corner, the site of station five, where Simone of Cyrene bears the cross for Jesus, right before they turn right, west, and vanish uphill for the rest of their journey.

And finally, as the sun is setting, the stores are closing, and just as we thought the day is coming to an end, it happens again. You see, Friday is also when the Jewish Shabbat will commence, in the evening. And just like the Muslims and the Christians, the Jews also have local synagogues that will fill up for the Friday afternoon Kabbalat Shabbat prayer. And again, since the holiest place for the Jewish people is on Temple Mount, and the closest place to Temple Mount for prayer is the Western Wall Plaza, many Jews will take the opportunity, if not every week, then occasionally, to experience Kabbalat Shabbat there. In Jerusalem there are many neighborhoods, and some are strictly inhabited by the ultra-orthodox Haredi community. Their stronghold neighborhoods, known as Mea Shearim and others, are situated just northwest of the Old City, just beyond what is known as the municipality road number 1. For the members of these communities, the easiest way to access the Western Wall Plaza by foot is to enter the old city via the Damascus Gate and follow our street, al-Wad, all the way to the Western Wall. This includes the 100 meters we have been watching all day. Here they come, all dressed in their nice and fancy Shabbat attire, adorned with a hat or animal fur shtreimel, giving away to which specific religious group they belong.

And here you have it, every week on Friday, on one little strip of 100 meters of a busy market street in the Muslim quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, groups belonging to three religions march though, each on their way to a religious spiritual event. Each on their way, and with no overlap. This was not set up by a government, or some multi-religious counsel. It is just a common practice.

This is not a story about just a ‘small miracle’ – it is about a miracle that against all odds takes place in a very specific place every week. It is the story ofJerusalem’s ‘Miracle Mile,’ the story of one little corner in Jerusalem where three religions have a unique shared existence between heaven and earth, or maybe we can call it heaven on earth.

[1] Josephus named it the Tyropeon Valley “Valley of the Cheesemakers” Wars 5.140