“Until the Final Furrow” – The return of evacuated Israelis to their frontier homes and the battle for the future of the spirit of Israel.

The renowned Zionist figure and hero Joseph Trumpeldor famously remarked, “Where the Jewish plow concludes its last furrow, that is where the border will be set.” This declaration is more than a mere geographical statement; it embodies both a moral commitment and a strategic necessity. The evacuation of Israeli citizens from their homes in the Gaza Strip and along the Lebanese border during Operation Swords of Iron, following the October 7th massacre, has shaken the Zionist ethos of “Until the Final Furrow.” Ensuring that these citizens can return home in full safety is essential for the future of Zionism and the State of Israel.

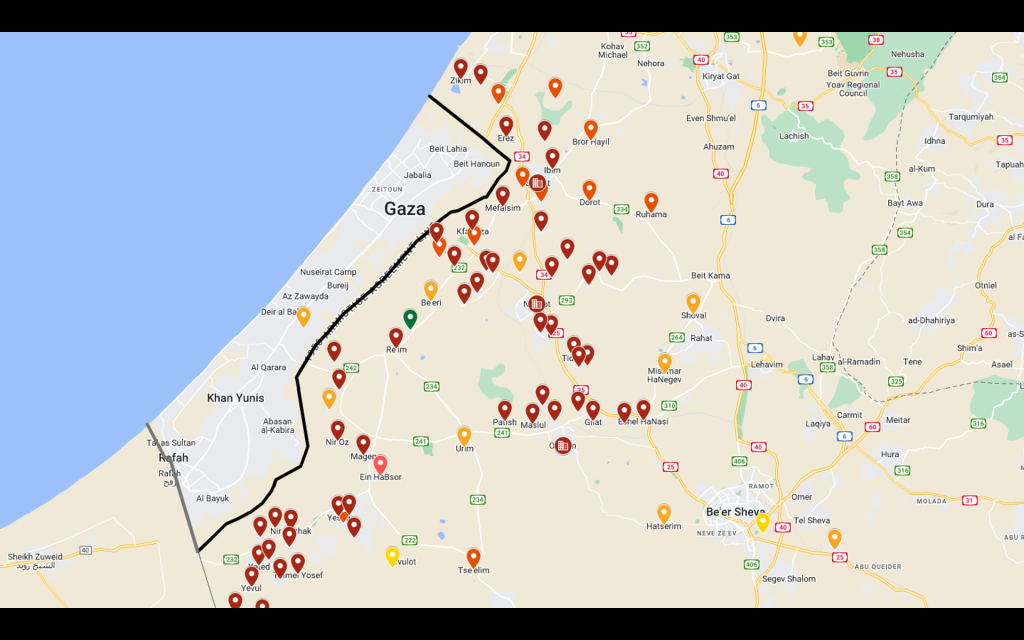

The October 7th massacre within Israel’s borders in the western Negev, followed by the war waged against Hamas in the Gaza Strip, has led to the evacuation of thousands of Israeli citizens from their homes in the region. Many were officially evacuated by Israeli authorities after their homes were declared closed military zones, while many others self-evacuated from frontline communities to safer areas.

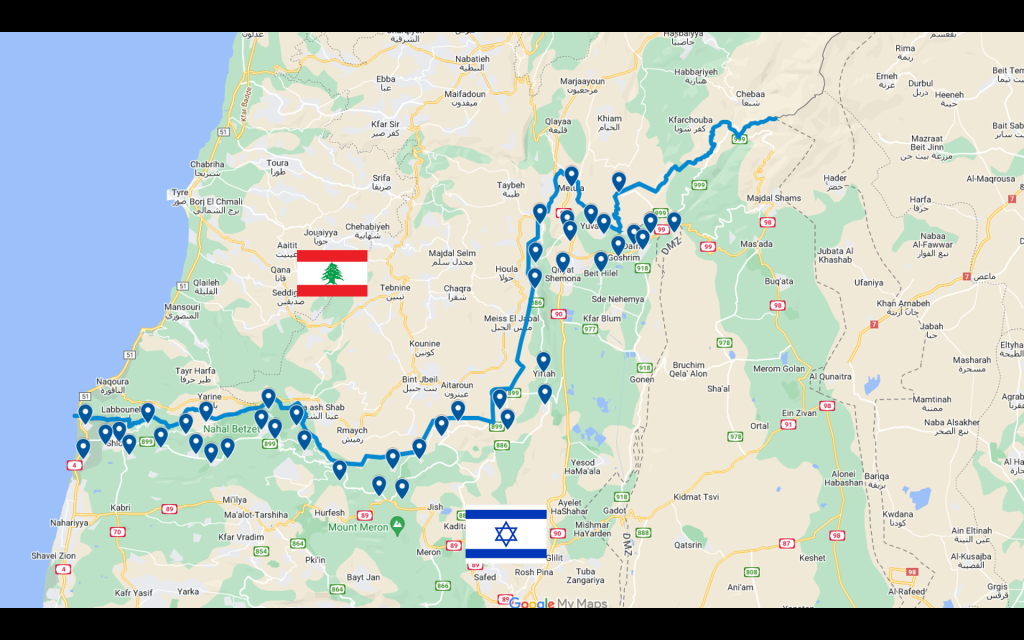

Since October 8th, when Hezbollah launched a violent offensive against Israel—attacking Israeli communities along the northern border with ballistic missiles, anti-tank missiles, and land-to-land missiles—Israel has evacuated citizens living in these areas. As in the south, many were officially evacuated by the authorities, while many others chose to leave on their own.[1]

First, I would like to comment on the terms that are used to define these people. In Hebrew the most common term is ‘מפונים’ – witch best translates to evacuated or evacuees. Also used is ‘עקורים’ witch best translates to “displaced persons” or “refugees.”[2] It refers to people who have been forced to leave their homes due to war, conflict, or other reasons, and are often seeking shelter or a new place to live.

I came across a book by Tamar Mor Sela, published in Hebrew in Israel, titled עקורים Akorim – October 7 Survivors on Life Without Home. The book contains 35 discussions with Israelis who were torn away from their homes, communities, routines, history, lives, and memories.

When opening the first page—the credits page—I couldn’t help but notice the book’s English title. The word עקורים was translated as Uprooted, and after reading the book, it became clear to me that Uprooted is the most appropriate word. It captures the deeply traumatic experience of being forced to leave a home and land to which one is intimately connected—where roots have been laid, memories built, and identity shaped. It is not just physical displacement but an emotional rupture, severing ties to a place cultivated with love, history, and belonging, leaving a profound sense of loss, uncertainty, and longing for return.

Will They Go Home, and When?

Will they go home? And if so, will that decision be entirely up to them, shaped by their personal experiences and emotions? While individual choice plays a role, the process of returning is dependent on several critical factors that must be in place before displaced families can rebuild their lives.

First and foremost, safety and security must be assured. No one can return to a home that remains under threat. Schools must reopen so that children can resume their education in a stable environment. Jobs and workplaces must be operational, providing people with the means to sustain themselves. Essential services and stores need to be restored, ensuring access to food, healthcare, and daily necessities. Additionally, government support and funding will be crucial in rebuilding communities, repairing damaged infrastructure, and providing financial assistance to those who have lost everything.

Returning home is not just about unlocking a door—it is about restoring a way of life. Until these conditions are met, for many, the question is not just when they will go home, but if they will ever be able to.

The government wants this process to move forward, and one of its steps toward achieving it is setting a deadline—as was March 1st, 2025—when the subsidy for living assistance was discontinued for many.

I would like to assert that we, the people and the state of Israel, need our brothers and sisters who have been evacuated from their homes on the frontier to return home. This is a collective need. This need does not diminish their personal right to live in their homes with dignity and safety, just like any other citizen of the State of Israel, regardless of where they live or call home. This need does not undermine the divine promise: “Every spot on which your foot treads shall be yours; your territory shall extend from the wilderness to Lebanon and from the River—the Euphrates—to the Western Sea,”[3] nor our right to settle there as stated in the Declaration of Independence of the State of Israel. It is a need to ensure that our collective Zionist spirit and the state of Israel do not vanish in the fourth quarter of its existence.[4]

It is essential to uphold the Zionist ethos of settling the land and cultivating it. To uphold the ethos of settlement,[5] agriculture, and prosperity is to preserve our natural rights over the land and to strengthen the security of the State of Israel. This ethos is encapsulated in the Zionist slogan “Until the Final Furrow.”

The renowned Zionist figure and hero, Joseph Trumpeldor, famously remarked, “Where the Jewish plow concludes its last furrow, that is where the border will be set.” This declaration goes beyond a simple geographical definition; it encapsulates both a moral commitment and a strategic imperative. And as he spoke, he acted. As one who arrived in the Yishuv with military background, Trumpeldor was sent to the upper Galilee, where four isolated Jewish communities were situated on the border between the British Mandate over Palestine and the French Mandate in Lebanon, to organize and strengthen the Jewish settlement in the region and develop its defense and agricultural potential.

On March 1, 1920 (the 11th day of the Hebrew month of Adar),[6] the Jewish settlement of Tel Hai, under the leadership of Joseph Trumpeldor, was attacked. In the battle, Trumpeldor and his comrades fought fiercely against a much larger Arab force. Despite their brave efforts, Tel Hai fell, and Trumpeldor was fatally wounded. His last words, “It is good to die for our country,” became a symbol of sacrifice and dedication to the Zionist cause. Trumpeldor and seven others were buried together in Kfar Giladi.[7] Years later, the Roaring Lion monument (HaAri HaSho’eg) was erected above their grave in their honor. The way the lion roars, with its head raised high, symbolizes strength and victory. When the city of Kiryat Shmona was later founded, it was named after the eight fallen defenders of Tel Hai.

The words of Trumpledor “Until the Final Furrow” will become a Zionist ethos that symbolizes unwavering dedication to cultivating and settling the land of Israel. It reflects the belief that agricultural labor, settlement, and perseverance are not just means of survival but essential to the fulfillment of the Zionist vision and the security of the Jewish homeland.

The Arab Revolt in Mandatory Palestine (1936–1939), later known as the Great Revolt, was a nationalist uprising by Arab Palestinians against British rule and growing Jewish immigration. It had two phases: the first (1936) involved strikes, protests, and attacks on Jewish settlements and British infrastructure; the second (1937–1939) escalated into armed conflict, including guerrilla warfare.

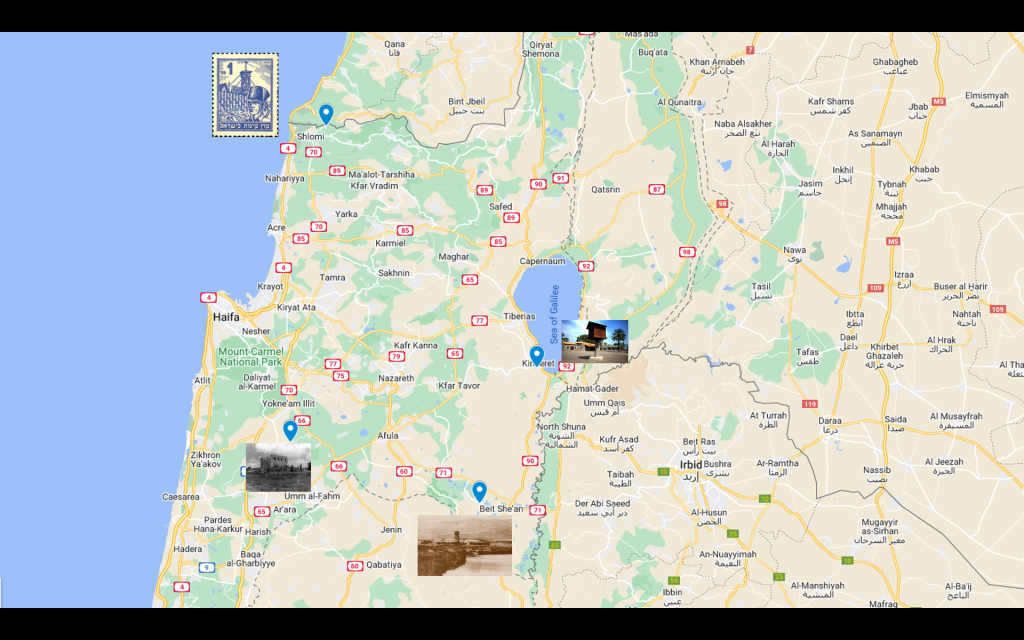

In response, Zionist pioneers developed the Homa U’Migdal (Tower and Stockade) strategy (1936–1939) to establish Jewish settlements in strategic areas despite hostility. Overnight, they built fortified agricultural settlements with a wooden watchtower and a surrounding stockade, making them difficult to attack. British law prohibited demolishing existing structures without legal proceedings, securing their permanence. This initiative led to over 50 new Jewish settlements, especially in the Galilee and Jezreel Valley, strengthening Jewish territorial claims and security, laying groundwork for statehood.

Plugot Sadeh (Field Companies), known as PoSh, were an elite Jewish strike force serving as the commando arm of the Haganah during the revolt. Hand-picked by Yitzhak Sadeh, they operated under British Mandate control as part of the Jewish Settlement Police. By March 1938, PoSh had 1,500 fighters in 13 regional groups, led by Sadeh and Eliahu Ben-Hur. They played a key role in the settlement of Hanita (March 21, 1938), one of the largest Tower and Stockade operations, securing a crucial defensive position along the Lebanese border.

In 1938, Nathan Alterman wrote “Zemer HaPlugot” (Song of the Platoons) at the request of his friend Yitzhak Sadeh. Composed by Daniel Samursky, it was revealed at PoSh’s first and only gathering and became its anthem. The song echoes Trumpeldor’s ethos “Until the Final Furrow” with the words: “No nation shall retreat from the foundations of its life.”

The fifth and sixth stanzas of the song read as following:

For not in vain, my brother, you’ve plowed and built,

This war is for our soul and our home!

Jo’ara,[8] Tel Amal,[9] Kinneret[10] and Hanita,[11]

You are our flags, and we are the walls.

For we will not turn back, and there is no other way,

No nation shall retreat from the foundations of its life.

There goes, there goes the company at night all in a row,

Your face, my homeland, goes with them unto battle!

The Hebrew phrase “אֵין עַם אֲשֶׁר יִסּוֹג מֵחֲפִירוֹת חַיָּיו” translates to “No nation shall retreat from the foundations of its life.” It is important to note that the word חֲפִירוֹת can be understood as ‘foundations,’ referring to the land on which they settled. However, it can also be interpreted as ‘trenches,’ symbolizing the places they dug into and where they would draw the battle lines, giving it a more military and security-focused meaning. This dual meaning reflects the essence of frontier communities—both the settlement and flourishing of the land, as well as being the frontlines of any future conflict.

It became increasingly entrenched in the leadership of the Yishuv and among the pioneers that frontier agricultural communities would determine the future state’s size and borders. These settlements would also serve as the moral justification and frontline bases for defending these areas when attacked.

The Peel Commission was a British commission of inquiry established in 1936 to investigate the causes of the Arab Revolt in Mandatory Palestine. After conducting extensive hearings and investigating the situation on the ground, the Peel Commission published its report in 1937, recommending, for the first time, a Partition Plan. The commission proposed the partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, with a British-controlled zone around Jerusalem. This was the first time the idea of partitioning Palestine was officially proposed. The Commission established the criteria for partition, which have remained largely unchanged since. It was proposed that areas with an Arab majority would be part of the Arab state, while areas with a Jewish majority, along with regions suitable for Jewish immigration, would be allocated to the Jewish state. For the Zionist leadership, it was clear that frontier communities would determine the future borders of the Jewish state. This marked a significant shift in Zionist political strategy. From that point on, Jewish settlement efforts intensified, focusing primarily on areas lacking Jewish presence to ensure their inclusion in the future Jewish state. Settlements were established in the Western Galilee, the Beit She’an Valley, the Ramot Menashe region, and the northern Negev to solidify Jewish claims to these areas.

In 1939, the “White Paper” was published, imposing severe restrictions on immigration and land purchases. The northern Negev was classified as land where acquisition was prohibited. As a result, the national institutions shifted their approach—settlement location was no longer just an agricultural question but a political one. Establishing communities in remote areas became a strategic effort to expand the country’s borders in preparation for any future challenges.

Less than a year after the publication of the White Paper,[12] Kibbutz Negba was established, the last of the 55 Tower and Stockade settlements built in response to British Mandate policies and Arab aggression.

By 1943, a series of kibbutzim had been established north of the arid zone, in relatively favorable locations: Dorot, Gat, Gevaram, Nir Am (which played a crucial role as a water supplier for the Negev settlements), Be’erot Yitzhak, Yad Mordechai, and the renewed Ruhama.

In 1943, a decision was made to push settlement efforts further into the desert, leading to the establishment of three outposts: Beit Eshel, Revivim, and Gvulot. Their purpose was to test the feasibility of settlement in the Negev and, just as importantly, to gauge the reaction of the British authorities.

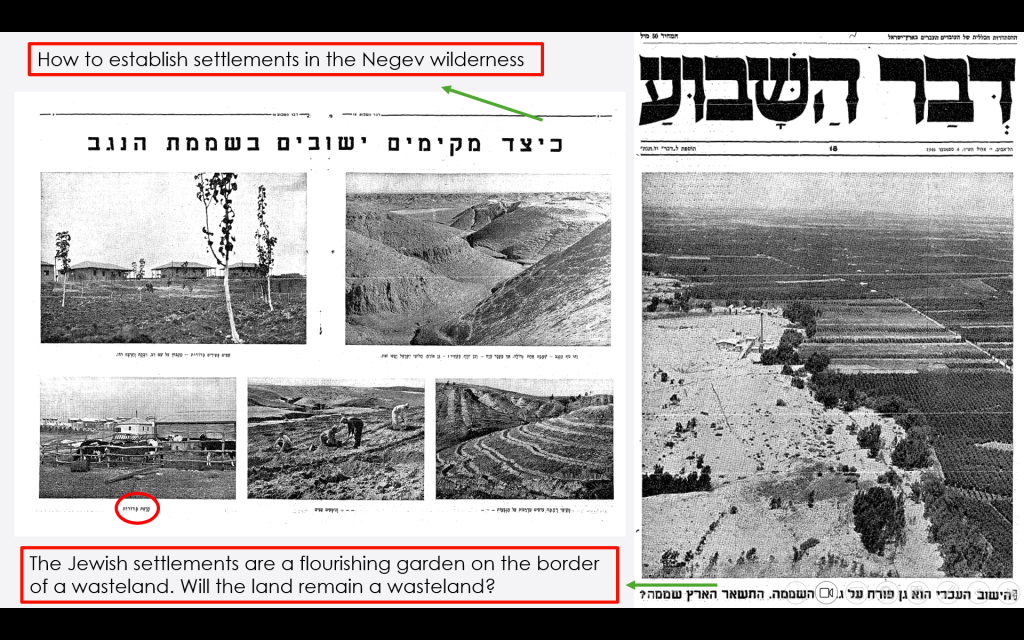

On Friday, September 6, 1946, the Davar newspaper published an additional supplement magazine, Davar HaShavua, which featured on its cover a picture of lush agricultural fields in the desert. The caption read, “The Jewish settlements are a flourishing garden on the border of a wasteland. Will the land remain a wasteland?”

One of the inside articles, titled “How to Establish Settlements in the Negev Wilderness,” featured pictures of the barren Negev Desert alongside images of Jewish communities in the region. These included homes, trees, and a cowshed in Kibbutz Dorot, pioneers planting trees, and a landscape of agricultural terraces created by members of Ruhama.

The 1946 Morrison-Grady partition proposal designated the Negev as a British-administered zone,[13] further accelerating Jewish settlement efforts in the region. This led to the plan for establishing 11 new settlements, which was secretly carried out on the night following Yom Kippur in 1946. The new settlements were: Urim, Be’eri, Galon, Hatzerim, Kfar Darom, Mishmar HaNegev, Nevatim, Nirim, Kedma, Shoval, and Tkuma.

One day later, on Yud Bet Tishrei (October 7, 1947), the front page of the Davar newspaper declared: “The settlements of the Negev have been redeemed from their isolation: Eleven new settlements in the southern Negev.”[14] This was followed by an article detailing the establishment of the settlements and a list of the eleven newly founded communities.

About a year later, in May 1947, a United Nations commission arrived in the country (UNSCOP – United Nations Special Committee on Palestine). During their tour of the Negev, they were deeply impressed by Nir Am’s water pipeline and the transformation of the desert into fertile land. In Revivim, they were astonished when they were presented with gladiolus flowers, freshly picked from a thriving field in the heart of the barren plains.

Jorge Garcia-Granados, one of the members of the commission, wrote in his memoirs:

“As we rode across this yellow desert, there was little enough to indicate any worth to this wasteland. Off in the distance lay our destination, where we were to have lunch- a Jewish collective settlement, Revivim. There were 17 Jewish settlements in the Negev, three established in 1944 to experiment with both dry and wet farming, and the remainder in 1946 and 1947. It seemed incredible that human beings could live in this desert. The sand was more silt than sand, and fine powdery dust which turned our eyebrows yellow and covered our faces with a thin coating of ochre. Our cars rode single-file and one could scarcely breathe in the dust we raised. Looking back, I could see it hanging ambient in the air long after we had passed: a yellow cloud of opacity, nature’s protest against this disturbance of a centuries-old desolation.

Then in the distance, a mirage appeared. A glittering blue opal of freshwater rose before our eyes. Under a harsh metallic sky it shone and sparkled like a huge jewel in the hot desert. It was water, fresh sweet water, the reservoir of the settlement. Then a collection of low, one-story white cement structures, surrounded by barbed wire with a fortress-like tower of stone in the center, came into view – and we are at Revivim….

I am sure our faces mirrored our astonishment. In sharp contrast to the desert, here lay a green carpet of soft grass and shrubbery. Fifty yards away the truck gardens began, rich with melons, cucumbers, tomatoes. We walked among pomegranate and olive trees, found ourselves in a plum orchard, and rested in the shade of young date palms; yet when we lifted our eyes, as far as the distant horizon, we saw only the sterile, rolling wadis of the desert, barren and empty, save for pigmy scrub brush with grew in disheartened little clusters here and there”. [15]

Joel De Malach, one of the founding members of Kibbutz Revivim in the Negev, was an agronomist and water engineer known for his pioneering work in desert agriculture and irrigation in Israel. He writes in his memoirs:

Representatives of the United Nations in ‘Revivim’:

“The line of vehicles stretched endlessly. It seemed that the Bedouins of the Azazma tribe had never seen so many civilian cars in the desert. The dust that rose began almost at Asluj and reached Tel Tsafim, five kilometers away. We tried to reduce the dust cloud by wetting an area of ground that received the obligatory name “parking lot.” A long line of tie-wearing individuals, presumably Americans and Europeans, descended from their cars, accompanied by a small group of kaffiyah-wearers dressed in black Eastern coats. Shortly after, photographers and journalists appeared. This was the ‘United Nations Special Committee on Palestine’ (U.N.S.C.O.P.), which had been recently formed to decide the fate of the land of Israel.

We received an advance notice. The day before, a nice woman, a clerk from the Jewish Agency’s political department, explained our role during the visit, which the institutions assigned great political importance to: we were to accompany each of the representatives from the various countries to explain, as best we could, that to develop the Negev, a population like ours was needed—one with a strong will and advanced technology. Fortunately, the tar pool was overflowing due to recent flooding, a fact that impressed all those present. It was a cool and beautiful day, common in the desert during transitional seasons.

The vegetable garden looked fresh and flourishing, and surprisingly, the gladiolus that had waited a long time to bloom blossomed all at once after the irrigation. The variety of colors stood out among the green vegetables, especially the bluish hue of the cabbages. Vegetables and flowers contrasted against the light brown of the desert.

The members of the delegation were deeply impressed. I was dressed in J.S.P. (Jewish Settlement Pioneer) uniform. I didn’t have a very military appearance among the flashes of the photographers. I picked two cucumbers, washed them, and offered them to the committee chair, Judge Sandström. I was disappointed to find that the judge was apparently unable to eat cucumbers without a plate, knife, and fork….

The next day, the visit to Revivim was prominently covered in the daily press, including the English-language Palestine Post. A photograph of the colorful gladiolus field made a great impression on the journalists and the representatives of the nations. Several months later, on November 29, 1947, during the famous UN vote, more than two-thirds of the UN Assembly representatives approved the committee’s proposal from UNESCO (of the countries that were members of the committee, only three opposed: Iran, India, and Yugoslavia). Some claim that the decision was made thanks to the gladiolus…”.[16]

In 1947 David Horowitz, a member of the Jewish Agency delegation to the United Nations., played a crucial role in advocating for Jewish statehood and served as a key liaison with UNSCOP (United Nations Special Committee on Palestine) during its investigation and deliberations on the future of Palestine. In his book he wrote:

“The tour of the Negev took place under the heavy and stifling heatwave, and the green island of Revivim in the heart of the desert, along with the water pool there, was truly a sight that revived souls. Here, once again, the creative power and capability of the Jewish people to transform a land that had eaten its inhabitants into a thriving land were demonstrated. More than anything, the image that etched itself in the memories of the committee members was that of the new man they encountered along the way—the young boy and girl in the kibbutz and the moshav, cultivating the land and drawing their sustenance from it.

For an entire day, our vehicles crossed the expanses of the Negev, engulfed in clouds of dust, heat, and the sun’s intensity. Sandström and Mohan, who rode in their car with Mc-Gilbari and me, looked tired and worn out, and Mohan even remarked with a hint of bitter sarcasm, “How nice it is that we weren’t tasked with investigating Saudi Arabia.” We smiled at the comparison that likened the Negev to Saudi Arabia and once again sank into our thoughts when suddenly green hills appeared before us—orchards, grass, hay, and above all, water: we had arrived at Ruhama.

This moment became etched in our memory as one of the most wonderful and impactful throughout our travels in the land. On the way, I showed the committee members the water pipe we had laid in the Negev, and in Nir Am, a group of irrigation experts awaited us, including Engineer Blas, the author of the plans for the Negev’s irrigation. We sat at a table adorned with maps of the land, and the experts presented to the committee members the vision of the grand irrigation plans that would bring the life-giving flow of water to the expanses of the Negev”.[17]

When the UN formulated its plan to partition Palestine into two states—adopted in the historic vote on November 29, 1947—the commission’s recommendations played a role, and the entire Negev was included within the borders of the proposed Jewish state. The “Until the Final Furrow” effort in the northern Negev, an isolated region with harsh conditions, contributed to the UN’s decision on November 29, 1947, to include it in the proposed Jewish state..[18]

David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, took it upon himself to define Israel’s security doctrine, one that in many ways still stands today.[19] During his leadership, he engaged in several instances of accelerated strategic thinking to study, learn, and contemplate his ideas about the security issues at stake—also known as “The Seminars.”

In all of his discussions regarding the security of the State of Israel, the Jewish and Israeli frontier settlements played a significant role. “Until the Final Furrow” would become, under Ben-Gurion, a strategic defense imperative for the State of Israel.

Following the War of Independence, in August 1949, the first ‘Defense Service Law’ was put forward in the Knesset. In his explanation of the law before the committee, Ben-Gurion stated:

“A security factor no less important and urgent is settlement and the balanced distribution of the population across the various regions of the country….

Moving immigrants to agricultural areas in the east, south, and around Jerusalem is not only a biological and economic necessity but also a security imperative. There is no need to reiterate here the wartime importance of border settlements in the Upper Galilee, the Jordan Valley, the Jerusalem hills, and the Negev. This calls for a national settlement plan”.[20]

Ben-Gurion further stated the four types of future security forces required under this bill:

- A small standing force. Permanent forces on land, air, and sea will serve voluntarily, under contract, and with employment conditions similar to those of other state workers.

- Recruits aged 18 to 26.

- Reserves. All individuals who served in the military, whether in mandatory or standing service, will remain in the reserve force until the age of 49.

- Frontier settlements. Residents of frontier settlements, living off their farms and work, will be specially equipped, trained, and fortified to serve as the first defensive barrier in the event of an enemy incursion.

In 1953, Ben-Gurion published a document titled “Army and State,” which would later be known as his 19-point document. Ben-Gurion reiterates the importance of frontier settlements:

“As is well known, our security does not depend solely on the army. Non-military factors will be just as decisive as military ones: the nation’s financial and economic capabilities, the professional skills of its workforce, industry, and agriculture, the flow of Aliyah, settlement in strategic areas near the borders, in the Jerusalem hills, in the Negev, in the “mixed” Galilee, the stock of food, raw materials, spare parts, transportation routes, and above all, the unity and spirit of the people”.[21]

“Until the Final Furrow” has been guiding the path for three generation of statehood and continues to do so.

Moshav Nativ HaAsara was initially established in 1973 as part of the Israeli communities in Sinai. As part of the Camp David Accords and the peace agreement between Israel and Egypt, it was evacuated and reestablished in 1982 at its current location, on the northern border between the Gaza Strip and the State of Israel. It is the closest Israeli community to Gaza. On October 7th, it was attacked by terrorists, and 20 members of its community were murdered by Hamas. Hila Fenlon, a resident of the moshav and a farmer, is among the few who have returned. These farmers, tied to the land, are back to continue. When meeting her on the moshav, her shirt, representing her farm, states: “The Future is Planted in the Land.” Hila is a true example of the living “Until the Final Furrow.”

Kibbutz Nahal Oz is located near the Gaza border, founded in 1951 as part of Israel’s efforts to settle the Negev region. It has played a significant role in Israel’s security strategy, serving as a frontline community that faces ongoing security challenges while maintaining its agricultural and cooperative way of life. On October 7th, the kibbutz was heavily attacked by Hamas terrorists, resulting in significant casualties and damage as part of the broader assault on Israel. The terrorists murdered 15 residents of the kibbutz and kidnapped 8 people, including women and children, taking them into Gaza.

On October 7th, Kibbutz Nahal Oz was prepared to celebrate its 70’s birthday, under the slogan “Ad HaTelem HaAcharon” – “Until the Final Furrow“.

In the spirit of Nahal Oz, the wall that protects the main access road to the kibbutz along Road 25 was adorned with this sign and slogan in salute to the entire kibbutz and farmers, who uphold the vision of Yosef Trumpeldor and till our land until the last furrow

The same banner, with the same artwork and statement, hangs outside the Nahal Oz tent in Hostage Square in Tel Aviv. In addition, the statement “Until the Last Hostage” was added in the same vein.

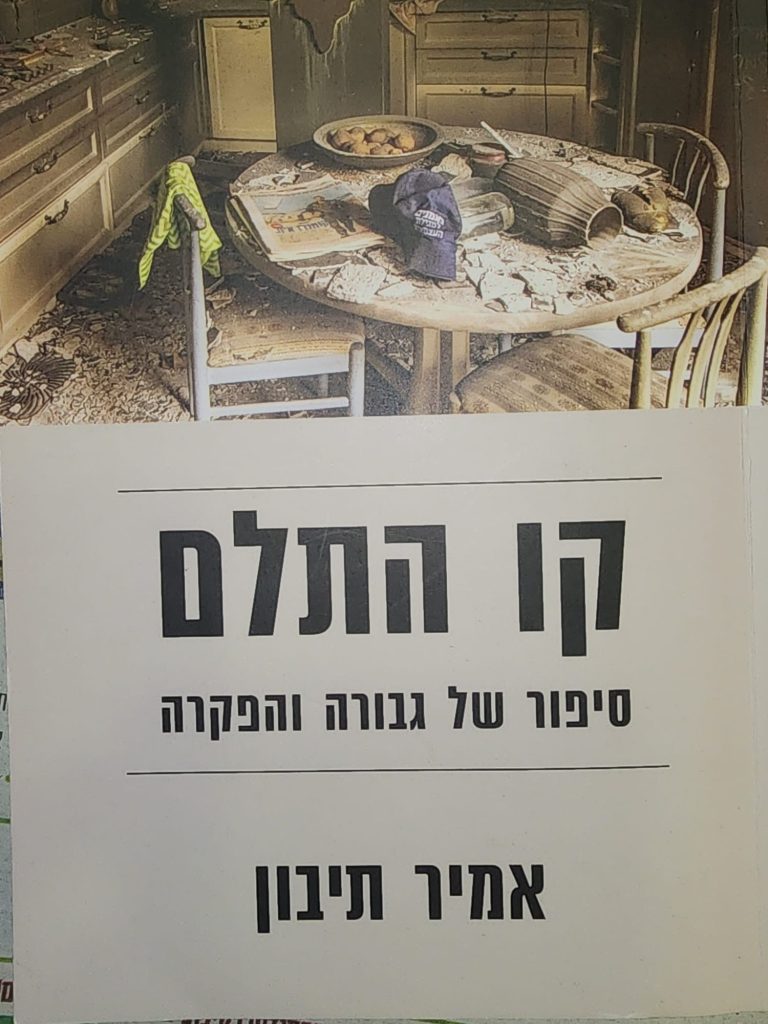

Amir Tibon is an Israeli journalist and writer, known for his insightful reporting on Israeli politics and Middle Eastern affairs. He is a member of Kibbutz Nahal Oz. During the October 7th attack, he was at the kibbutz while his father, Major General (res.) Noam Tibon, rushed down south and engaged in combat with the terrorists on his way to rescue his son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren. His book, titled in English The Gates of Gaza: A Story of Betrayal, Survival, and Hope in Israel’s Borderlands, was published after the attack. Its original Hebrew title is Kav HaTelem – Sipur Shel Gevurah VeHafka’ah – The Furrow Line – A Story of Heroism and Abandonment.

In a January 2025 issue of The Marker newspaper I stumbled upon, it focused on the changes and developments in the energy market. On its back page, a full-page advertisement featured the second agricultural convention of the Kibbutz Movement. Its title was “Ad HaTelem HaAcharon” – “Until the Final Furrow.”

A film that was produced about the agricultural farms in the Negev during the Swords of Iron war was titled “To the Final Furrow.”

Niv Tovia, manager of the Kibbutz Re’im orchard, was the Deputy Head of Security of the kibbutz on October 7th, where he was injured while protecting his family and the kibbutz. Like many other farmers in the region, despite the evacuation of the kibbutz, he has returned to maintain the crops and fields “Until the Final Furrow.”

For over 75 years of statehood, Trumpeldor’s ethos of “Until the Final Furrow” has become a cornerstone of Zionist values, passed down from generation to generation through education, stories, and actions. It embodies both a moral commitment and a strategic imperative. The State of Israel needs those who have been evacuated from their homes to return, live there in full safety, and rebuild and prosper. If this cannot be achieved, we must ask ourselves: What have we been working toward over the past 75 years of independence and 150 years of Zionism? Can we allow ourselves to abandon these values? It is much more than just worrying about the geographical implications of the next battlefield; it is about safeguarding our mission and our soul.

Now that this is established, we must ask ourselves: What needs to be done to ensure the return of the frontier communities in safety and dignity, and what can I do to help?

[1][1] Official figures report that a quarter of a million Israelis have been evacuated. However, many believe this number is inaccurate, as it does not account for those who self-evacuated from areas not included in the official evacuation zones despite their proximity to the borders. See INSS

[2] Displaced, In the global context, persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, either across an international border or within a State, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters. See here

[3] Deuteronomy 11, 24

[4] “The Land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people… . In recent decades they returned in their masses. Pioneers, ma’pilim, and defenders, they made deserts bloom, revived the Hebrew language, built villages and towns, and created a thriving community controlling its own economy and culture, loving peace but knowing how to defend itself, bringing the blessings of progress to all the country’s inhabitants, and aspiring towards independent nationhood… This right was recognized in the Balfour Declaration of the 2nd November, 1917, and re-affirmed in the Mandate of the League of Nations… The catastrophe which recently befell the Jewish people – the massacre of millions of Jews in Europe – was another clear demonstration of the urgency of solving the problem of its homelessness by re-establishing in Eretz-Israel the Jewish State…. On the 29th November, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish State in Eretz-Israel;… This right is the natural right of the Jewish people to be masters of their own fate, like all other nations, in their own sovereign State.

[5] Settlement and Resettlement in Zionist History and Ideology

Settlement is a central concept in Zionist history and ideology, aimed at returning the Jewish people to their land and establishing a Jewish state. These terms, which began to spread during the 19th century, were not only geographical processes but also ideological ones, with broad social and cultural goals. Resettling in the Land of Israel was one of the cornerstones of Zionism, which sought to establish a Jewish state and revive the Jewish nation through a return to the land and agriculture.

The Evolution of the Term “Resettlement”

The term “settlement” refers to the act of settling in a new place, particularly when populations move from elsewhere to establish permanent residence. In the Zionist context, “settlement” describes the process in which Jews established their homes in the Land of Israel, extending the earlier term “settlement”, which referred to the initial establishment of Jewish communities in the land. This process involved physical, economic, and social investment to build a vibrant and sustainable community.

During the Ottoman rule and the British Mandate in the 19th century, the term “settlement” referred to the organized Jewish settlement in Palestine at the time. The term “working settlement” referred to agricultural settlements focused on land work, while emphasizing socialist and egalitarian values.

Since 1967, the term “settlement” has acquired a political dimension, and today it almost always refers to Jewish settlement beyond the Green Line, making it closely aligned with the term “settlement”.

[6] The 11th day of the Hebrew month of Adar will be known as Yom Tel Hai, the Day of Tel Hai, and Yom HaHagana, the Day of Defense—the day the Jewish people stood up to protect themselves. Many significant events are connected to this date, such as the struggle to establish the Jewish settlement of Birya and the historic telegram sent by the Palmach Negev Brigade and Golani Brigade to the State of Israel upon conquering Umm Rashrash during Operation Ovda, the final operation of the War of Independence. The telegram stated:

“Transmit to the Government of Israel: On the Day of Defense, the 11th of Adar, the Negev Palmach Brigade and the Golani Brigade present the Gulf of Eilat to the State of Israel.”

[7][7] Six of whom were killed during this battle, and two during a previous attack (on January 20th).

[8] Jo’ara – the Haganah training center near Ein HaShofet: Between 1938 and 1948, it became the main military school for commanding officers of the Haganah and Palmach.

[9] Tel Amal, now known as Nir David, was the first Tower and Stockade settlement. On the 26th of Kislev, 5697 (December 10, 1936), during Hanukkah, the settlement operation was carried out.

[10] Kvutzat Kinneret is a cooperative group founded in 1913 on the shores of the Sea of Galilee and is considered one of the key milestones in the development of kibbutz settlement in Eretz Israel.

[11] Hanita – is a kibbutz in northern Israel, established on March 21, 1938, as part of the Homa U’Migdal (Tower and Stockade) settlement initiative.

[12] The 1939 White Paper was a British policy document that severely restricted Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine and limited land purchases by Jews, effectively abandoning the Balfour Declaration’s commitment to a Jewish homeland. Issued in response to the Arab Revolt (1936–1939), it aimed to appease Arab opposition but was widely condemned by Zionist leaders, who saw it as a betrayal, especially on the eve of World War II and the Holocaust.

[13] The 1946 Morrison-Grady partition proposal, published on July 25, 1946, was a British-American plan to divide Mandatory Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab provinces under continued British trusteeship. The plan was rejected by both Jewish and Arab leaders—Jews opposed the lack of full sovereignty, while Arabs rejected any form of Jewish autonomy.

[14] The term ‘Geulah’ – ‘Redemption’ has been associated with many Zionist and pioneering efforts in the Land of Israel. For example, Yehoshua Hankin was known as ‘Go’el HaAdamot’ – ‘Redeemer of the Lands,’ and the song Dunam Po veDunam Sham (literally: “An Acre Here and an Acre There”) by Yehoshua Friedman expresses this idea.

**“I will tell you, little girl,

and you, little boy,

how it is in the Land of Israel.

Land is redeemed:

A dunam here, and a dunam there,

clump by clump –

that is how we redeem our people’s land,

from north to south.”**

[15] Jorge Garcia-Granados, The Birth of Israel: The Drama As I Saw It, New York, 1948. Chapter Eight, Camels – And Politics, PP 84- 89.

[16] Joel De Malach, From Tuscan Hills to the Negev Desert, Ariel Publishing House, Jerusalem, 2007. (Hebrew). Pp 141-144.

[17] David Horowitz, State in the Making, Schocken Publishing, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1952. (Hebrew) pp. 201-202.

[19] Israel’s security doctrine is mostly defined by three main components: Deterrence, Early Warning, and Decisive Victory. In addition, defense and protection have become key components. Ben-Gurion always added additional components, such as values, a Jewish majority in Israel, and strengthening the settlements (Settlement Blocks, Urban Settlements, and Frontier Settlements). Settlements serve as the first line of border defense and establishment, providing physical and security-oriented strategic depth.

[20] The Sixty-Eighth Session of the First Knesset: Session 68, 20th of Av, 5709 (15th of August, 1948) – The Security Service Law (Ben-Gurion)

[18] The Beit She’an Valley is another region where this frontier settlement effort was successful. However, Jewish settlements in the Western Galilee, including Nahariya, Hanita, Eilon, Metzuba, Shavei Zion, and Yehiam, did not lead to the area’s inclusion in the Jewish state. Similarly, the Etzion Bloc and its four settlements, as well as settlements such as Kfar Darom, Nitzanim, Yad Mordechai, and Nirim in the south, along with Beit HaArava, Neve Yaakov, Kiryat Anavim, Ma’ale HaHamisha, and others, were also not initially designated to be part of the Jewish state.

[21] David Ben-Gurion, ‘Army and State’ (also known as the “18 Points Document”), which was presented and approved in a government meeting on October 19, 1953.