“Hi, my name is Zalman. You can call me Z, Zman, Zalman, or any combination from the first to the last letters of my name that catches my attention”. Many times, it is this way that I introduce myself to a new group of people I am going to guide. It is a bit humorous, gets the job done, and moves us away from all the questions like: Really? Is that your first name or last? What does your name mean? The best part is that most people catch on, and call me Z or Zman, the names I like.

My full name is Schneir Zalman, and I am named after my paternal great-grandfather. He arrived in Baltimore from Odessa in the beginning of the 20th century and opened one of the first Kosher poultry shops in the city, on the famous Lambart Street. He carries the name of the Alter Rebbe, the founder and first Rebbe of Chabad. I go as Zalman, as my mother wanted to differentiate me from two of my first cousins who are older than me, named after the same person, and go as Schneir daily. Little did she know that this would become a major problem once we made Aliyah (immigration to Israel), and I will grow up in a modern-religious Zionist Israeli environment. You see, in Israel of the late 80’s and 90’s the name Zalman was used as a slang word referring to a type of person, clumsy and useless. Many times, the word Zalman would be used as a nickname and slang for of the male genitalia. It did not matter if the other kids did or did not know our state had a president named Zalman, nor that there was a Big Rebbe with this name, over and over again my name was attached to the lyrics of the song “Zalman has pants, that reach to his knees, if his pants were to fall, then everyone will see his…Zalman, has pants…”. I think I really got over it, when my wife-to-be made the music of this song the ringtone of her Nokia cell phone, specifically for each time I called.

Names have been given since the beginning of creation. Adam had the first chance of naming every being of creation, among them the flora and fauna. And so he did, including his very own spouse- Chava (Eve). The creation was incomplete until it was given a name. In Hebrew the word ‘Neshama’ (נשמה) which represents our soul, incorporates in it the letters of the word ‘Shem’ (שם)- name. This recommends that names provide a window into the soul of a creature, or the assistance of the object it refers to. In other words, names are an extroverted representation of our being, of who we are. In a way, when parents decide on a name for their child, they are adorned with prophetic capabilities of looking into their child’s soul, or at the very least setting their child on a path of soul- name alignment.

Many of us carry names we were given because of the meaning they carry to our parents, family, and the cultural environment we were born into. Given to us by our parents soon after we are born. Young, with no understanding of the name, we grow to associate our name with ourselves as people refer to us. Some names are in memory of loved ones who passed away, some in honor of those alive. Some represent values or traits important to our society, and some are chosen because of their sound or meaning. Our names are personal on the one hand, and very much cultural and collective on the other, attaching us to our identity and culture, and a chain of history.

Early Zionism in Israel, in an effort to create a new type of Jew in the land of Israel, ‘the Modern Hebrew Jew’, insisted the newcomers change their names, with an emphasis on surnames. Ivrut, Hebraization, as it was called, was the demand to remove, and in some way to shake off, any scent and remanence of the ‘diaspora’ experience. Names were replaced with new names, names with a connection to the Land of Israel (tree names, landscape and sites and others), names that represent strength, rebirth, and future. Newborns were given names with meanings. Campaigns and outreach were widespread around the country, including in the Army, to encourage this change. Job positions, in particular government positions, were not able to be filled without following suit.

I think a lot about the survivors who arrived in Israel following the Shoah, Sh’erit ha-Pletah – the Surviving Remnant they were called, and had to deal with this social regulation request, and in many cases the requirement, of changing their names. For many of them, their names remained the last remnant of their loved ones they left behind. Generations that were severed, and no one left to bear their names. The name was the only thing left from their family, and by holding on to it there was an opportunity for rebirth, rebuild of the family dynasty. It is common to see in cemeteries in Israel on tombstones of Shoah survivors the words ‘Zichron Olam’, For Eternal Memory, or Martyr’s Death, followed by a list of names of family members who were left back there without a burial. Other people bear these names as a memorial and memory of what was. Loved ones, values, characteristics, worlds that were lost and need to be rebuilt.

Zionist narrative has produced the statement M’Soah L’Tkoma, which literally means from Holocaust to redemption. While the relationship between the horrors of the Shoah, the fate of European Jewry during world war 2, and the establishment of the state of Israel has been debated in many forms, and is clearly not a relationship of cause and effect, I personally much rather the statement ‘Shoah – Tkoma’, with a dash between the two words.

These names represent one aspect of the dash in the middle. After the holocaust, in the Land of Israel we rose and rebuilt the Jewish People. Those who came from there, the demand to leave behind their names, that complexity is in the dash (one of many). A complexity hard to bear.

It’s not a coincidence that many years latter through today, ‘Yom Hazikaron laShoah ve-laG’vurah, Israel’s Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day, ceremonies are titled ‘Each of us has a name’, highlighting the memory of individual victims through their names and stories. This title, lent from Israeli Poet Zelda, after one of her most famous works, has also been used as the name for Yad Vashem’s most important memorial initiatives, collecting all the names of the Jewish Shoah victims.

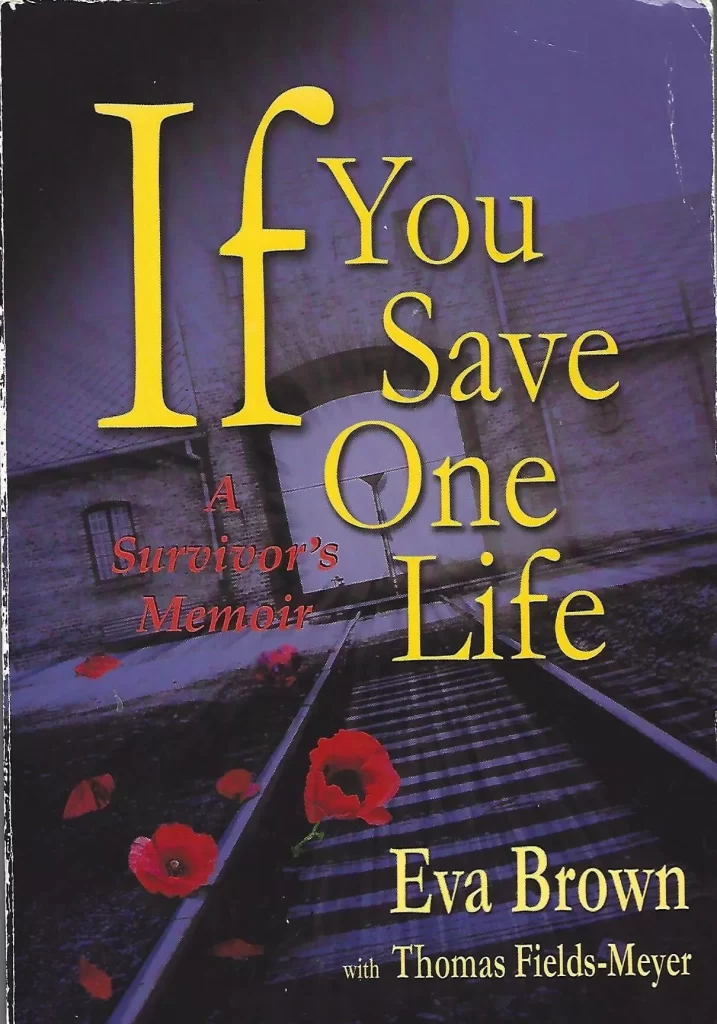

Shoah survivor Eva Brown opens her Memoir with the description of her fathers, Rabbi Solomon Rosenfeld- Shloyme, Rabbi of Putnok Hungary, siddur, their family’s treasure as she refers to it, which contained in the inside of the front leaf, “the Hebrew names of every living member of our extended family”.[1] At the end of her book she concludes with the following words “My treasured possessions are gone: Father’s war diary and his siddur- and nearly every beloved soul whose name he had written inside its cover. But I have this story.”

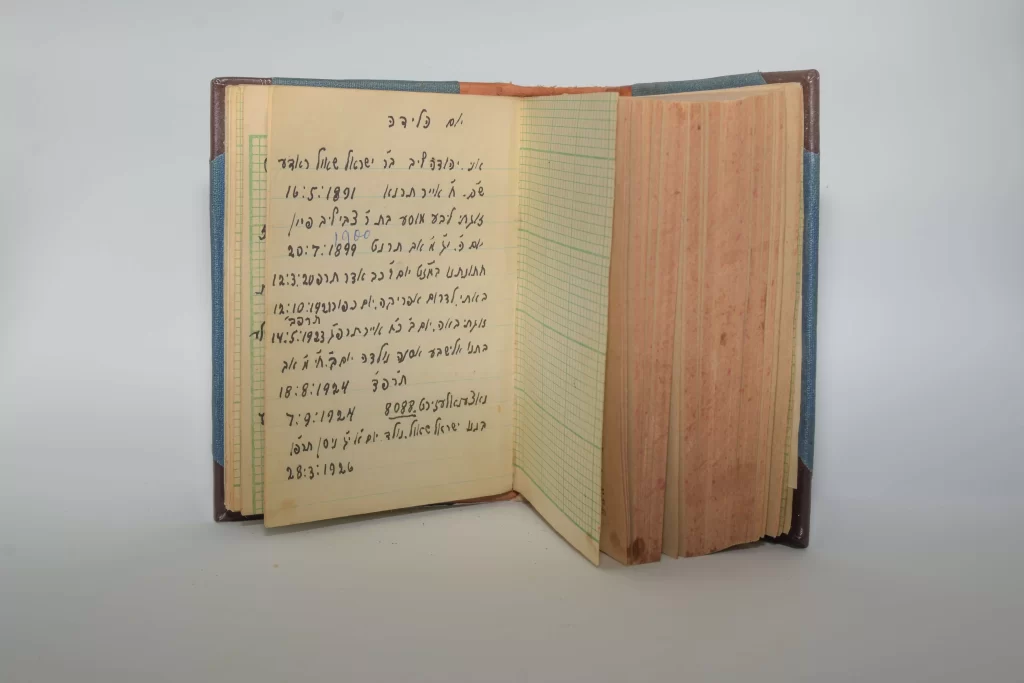

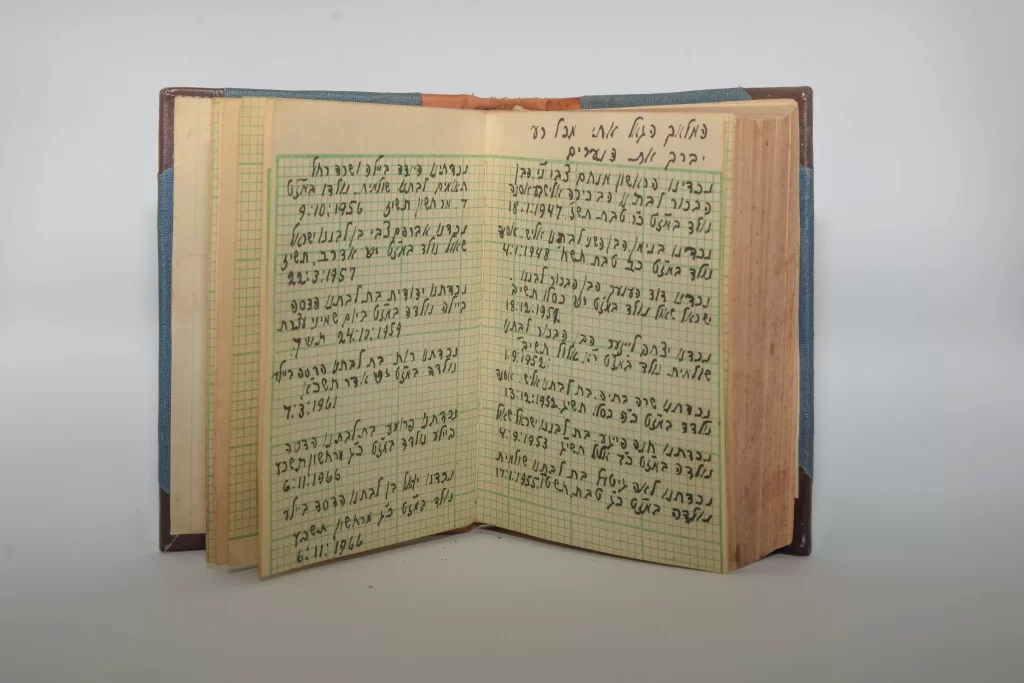

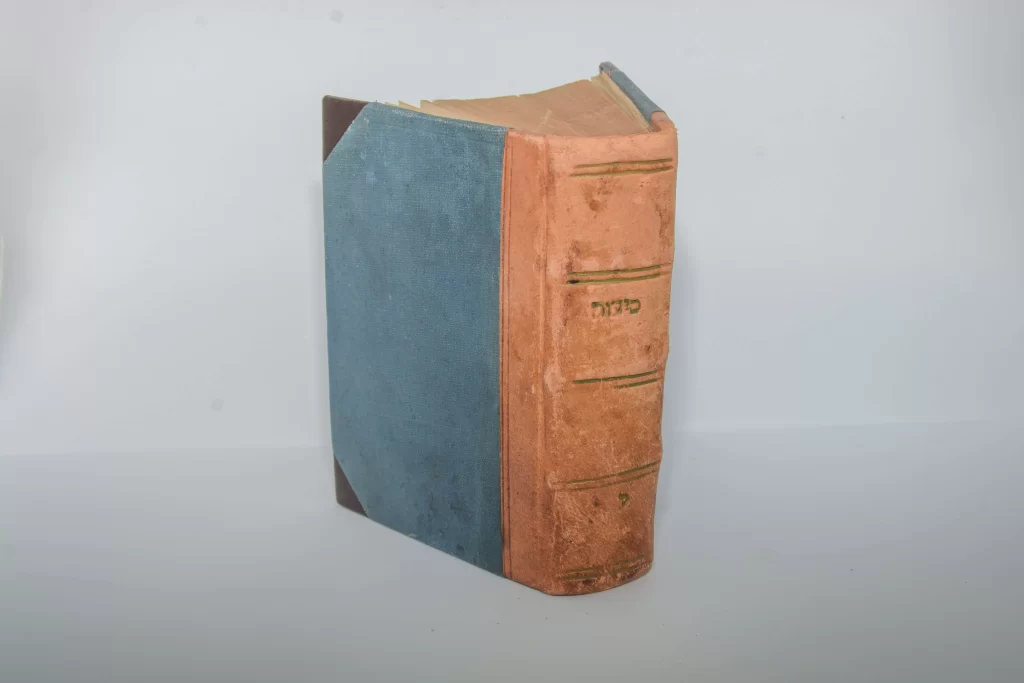

I too have a siddur. My maternal Great Grandfather, Reverent Yeuda Leib Rade of Johannesburg, too had a siddur. And just like Eva’s father, he too, entered on the cover in his own handwriting, names, and dates of importance regarding his life. The majority of the names and dates have to do with the birth of family members, and other smachot, celebrations, such as family weddings, and on the contrary, dates loved ones of the family have passed away- Yizkor days . The reason for it being in his siddur, is in addition to serving as a family tree list, to serve as a list for prayers and blessings. I believe he would look at it every time he used it to pray, which was 3 times a day. Through his prayers he applied special Kavanah, intentions, meditations, or blessings for his family members.

The Rabbis teach us Vayikra Rabbah 32, 5 (Shir HaShirim Rabbah 4:)

”Rabbi Hun stated in the name of Bar Kappara: Israel were redeemed from Egypt on account of four things; because they did not change their names…’They did not change their name’, having gone down as Reuben and Simeon, and having come up as Reuben and Simeon. They did not call Reuben ‘Rufus’ nor Judah ‘Leon’, nor Joseph ‘Lestes’, nor Benjamin ‘Alexander’.

Carrying a name is much more than a symbol of recognition, it has the power to shape our identity while connecting us with our past generations and the values that have been passed down and leave an individual recognizable mark for the future.

And yet, when we had kids, the weight of my name, the Zionist ethos, and the new fashion of creative modern names, led us to abandon our family names and adorn our kids with Hebrew names, some would say Israeli names, that we found had significant meaning.

Our first-born son we named Amit Shalem. Amit, has become a very popular name in Israel for boys and girls alike. Amit means friend and Shalem means complete. We blessed him that he should always be in a true and complete friendship with himself, his surroundings and with God. In addition, Shalem is one of the many names of the city of Jerusalem. Keeping Jerusalem close to us at all times is in our minds empowering, and to our pleasure Jerusalem has become not just a reference but a substantial and significant part of Amit’s life.

Our daughter Eden was born in California while we were surviving as educational Schilcim, emissaries, for the Jewish Agency for Israel. She was born during the summer while we were on staff at Camp Ramah CA. Many times, I go back to the moment we publicly named her. She was four days old, and it took place in the BKR, Beit Knesset Ramah. With fellow staff, campers, and friends we have made over the years, we celebrated together her coming into the world. It was a celebration and a ceremony, a ceremony we created just for her. Eden is the name of the Garden where God created Adam and Eve, and where they lived before their sin. The garden of Eden is that place we all strive to reach at the end of our lives, where our souls reconnect with the eternal, with complete goodness. Eden is also part of the Hebrew word Adinut, which means gentle, softness. We pray Eden will bring much needed gentleness and softness into this world during her lifetime. It is through gentle acts of kindness that we can reach Gan Eden, not only in our afterlife, but we can create it here on earth during our lifetime.

Noam Shalom, our third son. Noam has been at the top of the most popular names in Israel for the past couple years. Our Noam’s name is inspired by the biblical verse “Its ways are ways of pleasantness, and all its pathways are peace” Noam = pleasantness, and Shalom = peace. The Torah, the Jewish law, is described as Darchei Noam and Darchei Shalom, paths of pleasantness and peace. The Rabbis teach that the Jewish way of life is, VeChai Bahem, you shall live by it, therefore the law of the Torah should bring pleasantness and peace into the world. Jewish law does not require to perform acts that bring loss in the world, that are dangerous and damaging, on the contrary they must bring life. For thousands of years Jewish Rabies and leaders have debated the Jewish law regarding all walks of life, they have applied logic, debate, and tools in order to reach their ruling. Two of these tools are called “Derchai Noam” and “Derchai Shalom”. They are applied when the obvious ruling might create a difficult situation. For example, between a Jew or the Jewish people and their non-Jewish surroundings, or between and a husband and wife. Applying these tools allow the rabies to defer from the obvious in order to maintain pleasantness and peace in the world.

Sometimes things are black and white, clear, and easy to decide and rule on. Yet the question is how the ruling meets the community. With applying special tools that allow us to look beyond the obvious, some would say the just, ruling, we are able to create a tolerant and inclusive society. We pray Noam will be a contributing force in this world and will apply these much-needed skills in order to bring the world closer to peace.

Ayellet-Chen, our youngest. Our generation has been blessed with the ability to learn, unify, and practice traditions and customs that have developed throughout the Jewish world during 2000 years of diaspora. Each diaspora and its customs. This is due to the ingathering of the Jews from around the world in Israel, modern communication, and research. For instance, the synagogue in our community combines traditions and customs from both the Askanazi and Mizrahi world.

Ayellet-Chen is named for a 17th century piyut by Rabbi Shalom Shabazi from Yemen. Ayellet is a doe, a young deer, and Chen is beauty with an emphasis on internal beauty rather than external beauty. Ayellet-Chen is inspired by the verse “A loving doe, a graceful mountain goat” (Proverbs 5, 19), it is a song about the love between the Shekhinah, the Divine presence in the female form and the people of Israel. It has also become a song about the love of a man to his Torah. In the Yemininte tradition it is most popular as a love song between a groom and his bride, traditionally sung under the chuppah, wedding canopy, and during the seven days following the wedding, sung while accompanying the groom on his walk from the synagogue to his home. Ayellet-Chen, as the Shekhinah, Torah or Bride is the spiritual power holding up the world, bestowing comfort and strength to those in exile, those setting in the dark. She is welcomed in the courts of Kings, and applies Love, Chen, Chesed (Grace) and Bina (Wisdom).

We bless Ayellet-Chen with the ability to bring divine presence into the world. Young, free, and light as a Dow, she should spread her Chen around the world, and be a source of comfort and wisdom to the world.

The Rabbis teach us (Midrash Tanchuma, Vayakhel 1)

Every time a man increases the number of good deeds he performs, he adds to his good name. You find that a man is known by three names: the name by which his father and mother call him, the name by which other men call him, and the one he earns for himself; the most important name is the one he earns for himself.

“Hi, my name is Zalman. You can call me Z, Zman, Zalman, or any combination from the first to the last letters of my name that catches my attention. My paternal great-grandfather was Schneir Zalman, and my children are Amit, Eden, Noam and Ayellet-Chen”. We are continuing our family chain, and hopeful adding a thick and meaningful link, to pass on our heritage to the generations to come, and bring the world to a better place, each as their name and nesham (soul) reach.

[1] Eva Brown with Thomas Fields-Meyer, If You Save One Life: A Survivor’s Memoir, Los Angeles 2007, Pp 18-19