I’ve been asked about my perspective on visiting Israel amidst the current challenges, following the October 7th massacre, the ongoing conflict with Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and increased tensions in the West Bank. There’s a specific interest in my thoughts on ‘solidarity missions’ tied to these events and the overall Israeli society situation.

In a nutshell, my response would be a firm affirmative – you should definitely plan a visit. While acknowledging that traveling to Israel now is more intricate compared to typical destinations, the complexity should not be a deterrent. On the contrary, these circumstances make it even more crucial to visit Israel during these challenging times. You must allocate the time and resources to experience the reality on the ground.

In today’s world, staying updated in real-time with events in Israel is easily achievable. With a simple click, financial support can be swiftly extended, and arranging a video chat with friends and family worldwide for a comforting conversation is just as effortless. While these actions are valuable and greatly appreciated, there’s an irreplaceable significance to having boots on the ground.

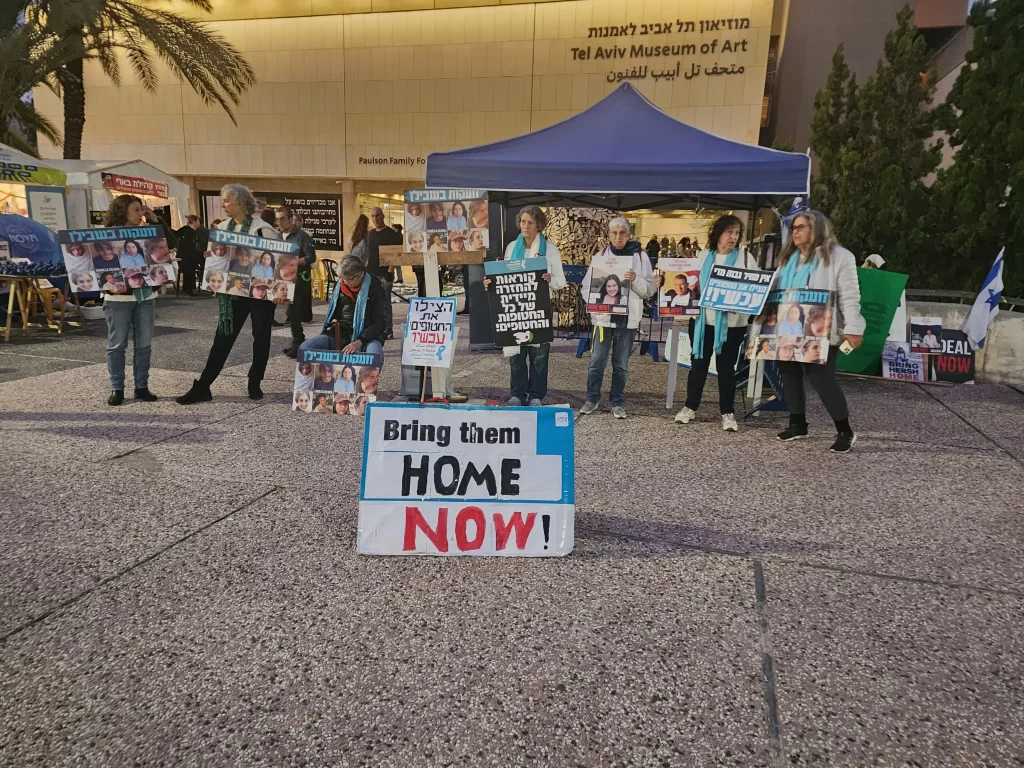

For Israelis, the gesture of individuals coming from different parts of the world and declaring, “We are here,” holds profound meaning. It goes a long way in providing a sense of support. I would like to offer a broader perspective before delving into the importance, focusing on the actions undertaken during these visits, we may find a clearer connection to the underlying significance.

I would like to start with a big picture thought, and then to focus on what is done during these visits – and maybe through these actions we can relate to the why easier.

During the era of the Jewish temple in Jerusalem, Jews would journey to the city, particularly during the three pilgrimage holidays known as Chagim[i] – Pesach (Passover), Shavuot (Weeks/Pentecost), and Sukkot (Tabernacles). This pilgrimage was a commandment outlined in the Torah: “Three times a year—on the Feast of Matzoth (Unleavened Bread), on the Feast of Weeks, and on the Feast of Sukkoth (Booths)—all your males shall appear (yeira’eh) before your Lord God in the place that [God] will choose. They shall not appear before the Lord empty-handed” (Deuteronomy 16:16).[ii] The term “yeira’eh” signifies the obligation to be seen in the temple courtyard, symbolizing a personal presence in the place chosen by the Creator to dwell among His people.[iii]

Derived from this verb, the mitzvah is known as mitzvat re’iya, encompassing the act of appearing with a korban (sacrifice), specifically the olat re’iya (pilgrimage burnt offering), which was entirely consumed in the altar’s fire. This ritual was complemented by two additional sacrifices – Shalmei hagiga (pilgrimage peace offering) and shalmei simha (festive peace offering). At the core of this pilgrimage was a profound spiritual encounter between an individual and their God.

The Talmudic Rabbis have supplemented that “based on the way the verse is written, without vocalization, it can be read as ‘yireh,’ signifying ‘Shall see,’ instead of ‘yera’eh,’ meaning ‘Shall appear.’ This conveys the notion that just as one comes to see, similarly, one comes to appear.” The interaction that unfolded on Temple Mount, within the temple courtyard, constituted a reciprocal experience of both seeing and being seen.

Apart from the encounter with the Creator during the pilgrimage, individuals would also come across their fellow people and nation. Many pilgrims would journey from various regions within the land, and perhaps even from different parts of the empire.

Historical and rabbinical sources, coupled with archaeological findings and research, provide insights into the congregation of our nation in Jerusalem, their sacred city. As a tour guide, I attempt to envision the logistics of lodging, dining, and transportation required during these periods. Municipal preparations involving security, police presence, stewards, ushers, street maintenance, and sanitation matters are also considered. However, paramount among these considerations is the interpersonal connection that unfolded among the people on their journey to Jerusalem and within the city itself.

As a guide, one of the most thrilling locations in Jerusalem for me is the remnants surrounding the Temple Mount. The streets and markets served as gathering points for Jews before and after their visits to the Temple. I can envision rabbis engaging in teaching and passionate debates on ideological and halachic (Jewish legal matters) topics. The lively discussions in the streets covered heated issues such as predetermination, the concept of life after death, matters of purity and impurity, and political perspectives on the relationship with authorities, whether it be the Roman Empire and its representatives or the local rabbinic and priestly leadership, among other compelling subjects.

Discussions and topics that arise when Jews from various parts of the world come together often begin with the customary Jewish geography inquiry: “Where are you from? Do you know…?” Conversations extend to diverse subjects, such as what their respective Rabbis discussed in synagogue last week, how their communities collaborate with non-Jews, thoughts on combating antisemitism, details about their children’s schools or Yeshivas, and updates on Jewish communities worldwide, including places like Alexandria, Babylon, London, New York, and beyond.

This gathering in Jerusalem served as the nexus for the Jewish world, where crucial updates and gossip were exchanged both before and after the pilgrimage to the Temple, where individuals met the Creator of the universe. However, beyond being a mere information exchange, it embodied a sense of solidarity – an opportunity to comprehend the circumstances of other parts of the nation and respond to them. The pilgrimage to Jerusalem and the holy temple established a system of social awareness, care, and compassion towards fellow Jews.

Here are a couple of examples illustrating how this manifested during the pilgrimage visit to Jerusalem.

Tzedakah, the act of helping those in need, is not merely a charitable gesture but rather an obligation to uphold justice, as the term is derived from “Tzedek,” meaning justice.[iv] The Rabbis instruct us in Mishnah Shekalim 5:6 that:

“There were two chambers in the Temple, one the chamber of secret gifts and the other the chamber of the vessels. The chamber of secret gifts: sin-fearing persons used to put their gifts there in secret, and the poor who were descended of the virtuous were secretly supported from them. The chamber of the vessels: whoever offered a vessel as a gift would throw it in, and once in thirty days the treasurers opened it; and any vessel they found in it that was of use for the repair of the temple they left there, but the others were sold, and their price went to the chamber of the repair of the temple.”[v]

As individuals visited the temple, they would come across chambers or, if you will, tzedakah boxes. These encounters compelled pilgrims to take notice of the circumstances of their fellow Jews and respond, in this case, through acts of Gemilut Hasadim (loving kindness) by contributing to tzedakah.

The physical stairs discovered on the southern side of Temple Mount, referred to as the southern steps, served as the primary entrance for pilgrims to the Temple Mount. These steps not only provided access but also indicated a deliberate system to foster awareness. The intentional irregularity in their layout, featuring alternating narrow and wide steps throughout the entire staircase, prevented individuals from running up or down hastily upon entering or leaving the temple. This design encouraged a thoughtful approach, emphasizing that one must contemplate their visit and refrain from rushing to depart, symbolizing a moment to see and be seen by the Creator in the temple.

The Rabbis instruct us that the entry was from the right, and the exit was from the left. This directional flow wasn’t confined to the entrance gate alone; it encompassed the entire traffic system during the visit to the temple, following a circular motion as suggested by the term “L’Chug” – meaning to circle or encircle. Pilgrims would ascend from the south towards the north. Upon reaching Temple Mount, they would turn to the right and proceed east, then veer to the left towards the west, advancing through the courts from east to west. Ultimately, they would turn left again towards the south, departing Temple Mount from the southern side.

The rabbis teach in Mishnah Middot 2:2:[vi]

“All who entered the Temple Mount entered by the right and went round [to the right] and went out by the left, save for one to whom something had happened, who entered and went round to the left. [He was asked]: “Why do you go round to the left?” [If he answered] “Because I am a mourner,” [they said to him], “May He who dwells in this house comfort you.” [If he answered] “Because I am excommunicated” [they said]: “May He who dwells in this house inspire them to draw you near again,” the words of Rabbi Meir. Rabbi Yose to him: you make it seem as if they treated him unjustly. Rather [they should say]: “May He who dwells in this house inspire you to listen to the words of your colleagues so that they may draw you near again.”

Within our temple or community center during peak times, we have established a physical system that compels us to acknowledge others, especially those in need. The Rabbis emphasize that it is not enough to merely recognize individuals facing challenges; we must also acknowledge them and respond appropriately. This includes mourners, those who are excommunicated, individuals with a sick person in their house, those who have lost an object, and bridegrooms.

Returning to the Aliya Laregel, the Jewish people’s pilgrimage to Jerusalem during the three Chagim holidays, we can now comprehend the mitzvat re’iya. The commandment to yireh – yera’eh, meaning Shall see – Shall appear, signifies, on one hand, a connection to the Creator of the world (Covenant) and, on the other hand, a connection to our fellow Jews (Peoplehood).

Understanding this age-old practice, I believe these principles should serve as the foundation for all our communities, where we establish structures that compel us to truly see others and respond appropriately.

I believe this concept should be the foundation for visits to Israel, particularly solidarity missions, today. A visit to the state of Israel should serve as a conduit for a direct, personal mifgash, or meeting, between individuals across our nation. This encounter should foster a heightened sensitivity to recognize each other’s needs and provide opportunities to respond in a meaningful and appropriate manner.

By examining the engagements and activities that transpire during these trips, we can identify various types of interactions that will function as our steps to the temple- meeting place where we truly see each other and recognize their needs.

Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel once stated, “When you listen to a witness, you become a witness.” In today’s hyper-media world, we are all witnesses to events due to the pervasive real-time coverage and footage that encapsulate every facet of our lives. The October 7th massacre and the subsequent war have been extensively covered and filmed, yet it remains our individual responsibility to personally bear witness and gather testimony of the atrocities suffered by our people. Waiting for organized trips to memorial sites 50 years later should not be the only option when firsthand witnessing is possible. How do we achieve this? Let the field speak – and listen. Visit the sites with your own eyes and lend an ear to as many survivors and parties involved as possible. This includes victims, survivors, and their families, as well as the fighters and heroes who rose to defend civilians and the state of Israel. Connect with comrades, friends, and families of the fallen, along with first responders, medical teams, ZAKA, therapists, and anyone with firsthand experience.

Listening to testimonies and bearing witness not only validates the individuals sharing their stories but also empowers and emboldens them to confront anyone who challenges their experiences. It imposes on us the responsibility to share their narratives and advocate on their behalf, ensuring that their personal needs are addressed to the best of our abilities, justice is pursued, and lessons are gleaned. Moreover, this endeavor equips us with knowledge and emotions that serve as a defense against deniers, both present and those likely to emerge in the future.

Listening to testimonies and bearing witness is the initial step, preceding any discussion about providing solace. The enormity of the atrocities during the October 7th massacre and the ensuing war is overwhelming to fully grasp. Before extending comfort, we must descend into the depths with the victims and survivors, standing beside them in their darkness. Only by sharing in the experience can we begin to offer a supportive hand to lead them out. This is achieved through firsthand, uncensored, and unfiltered testimony.

I propose consistently introducing yourself by sharing your background, origin, and purpose. Making a personal appearance and conveying not only your individual message but also the message of the global Jewish family can have a profound impact. Saying, “We are members of the Jewish community from/ we are Jews/Christians from, and we came to Israel to stand with you/to hear your story/ to listen/ to say Thank You” holds significant weight. This holds true whether you are interacting with survivors and their families, soldiers, bereaved families, Sheva homes, or any Israeli on the street. The gratitude felt by Israelis towards each person who dedicates time, makes a financial commitment, and travels to Israel is immeasurable. This gesture of comfort resonates deeply on an individual people-to-people level and contributes to shaping the future of the Jewish people.

I cannot think of anyone in Israel who hasn’t been profoundly affected by the October 7th massacre and the ongoing war. While I’m about to address visiting wounded soldiers, I believe the broader lessons can be applied more widely.

When guiding groups to visit wounded soldiers in hospitals, I adhere to the practice of preparing them for the Bikur Cholim—the mitzvah of visiting and aiding the sick. This is a significant mitzvah that requires appropriate preparation. While I am neither an expert nor formally trained for this, my role as a guide and educator over the years, coupled with the privilege of participating in solidarity missions during past wars, has shaped my practices.

Approaching visits to wounded soldiers or victims of terror requires a humble mindset, recognizing the uncertainty of their ever-changing state. These soldiers were once in peak physical and mental condition, engaged in the most significant mission of their lives. Now, their reality is markedly different, grappling with unforeseen physical and mental challenges for which they were unprepared.

Upon entering their room, it’s crucial to acknowledge our lack of knowledge about their current condition. They may be pre or post-surgery, just receiving news from a doctor—whether positive or negative—experiencing pain, or grappling with concerns about friends, comrades still in battle, or their family by their side. Before entering, obtaining permission from medical staff, family, and the soldier is essential, recognizing that they may not be ready for interaction.

Upon introduction, clearly state who you are, your representation, place of origin, and the purpose of your visit. Israelis greatly appreciate and are often surprised by the effort taken to visit them. Some soldiers may choose to discuss the circumstances of their injury, medical procedures, and rehabilitation, while others may prefer not to delve into those details. Allow them to guide the conversation, pose questions with care, and demonstrate genuine interest.

Express gratitude for their sacrifice and offer encouragement for a prosperous future. Instead of making assumptions about their recovery, refrain from using phrases like “very soon you will be up and running again.” Instead, acknowledge their challenges by saying, “You are brave and strong; we are confident that you will be successful and have a bright future. We look forward to staying in touch and witnessing you accomplish your new goals.”

Extend comfort and gratitude not only to the wounded soldier but also to their crucial support circles—family members, parents, spouses, children, boyfriends, girlfriends, and friends. Additionally, express appreciation for the dedicated medical and support staff at the hospital, recognizing their tireless and holy work in caring for our soldiers. Each person deserves individual recognition.

Before departing, in line with our Jewish tradition, some may wish to offer a prayer for healing or share spiritual words. However, it’s essential to be mindful that Israeli soldiers come from diverse backgrounds, with varying levels of observance and religious practices. It is advisable to ask, “Would you like to receive a prayer with us?” to accommodate everyone, and you may find that many are moved by this considerate inquiry.

Upon leaving a room, take a moment for reflection before entering another. This pause allows you to process your visit and, I believe, leave with a sense of hope and pride.

Consider the broader context. Every Israeli has been profoundly affected, and the emotional state of those we interact with remains unknown from the moment we arrive until our departure. They might have encountered personal losses, be acquainted with individuals in captivity, or have close friends and family actively serving or on reserve duty. The intricacies of their experiences are unpredictable, urging us to approach each and every one with care and sensitivity.

Teachers and therapists, a vital force in our society, continuously work to educate and treat the majority of our population. Often, they return home to sons and daughters, husbands and wives who are serving in the army. In some cases, they may have also experienced personal losses. Engaging with them, with their permission, and offering compassion, empathy, and support is essential.

Some of the most challenging events to attend are funerals and shiva homes. I sincerely wish, hope, and pray that we won’t have more of these occasions. If you can attend, in my view, it goes a long way and has an impact beyond measure. I can’t emphasize it enough: Saying, “My name is…we came from…to say thank you/give a hug/support…” goes a very long way. Through this, we convey a message of gratitude and support, essentially voting with our feet. We are expressing that the entire people of Israel stand with you. It’s crucial to carry this encounter with you, share it, and let it inspire you to continue finding your way in contributing to the mission of ensuring the ongoing existence and prosperity of the Jewish people and the State of Israel.

Get under the stretcher, supporting Israeli society through every challenge that awaits us. Since the October 7 massacre, Israeli society has risen to every challenge in an unprecedented and astonishing manner. Preexisting organizations and many new and emerging ones have mobilized thousands of citizens through volunteering projects that have addressed every need—supporting soldiers, aiding victims, providing housing, clothing, education, agricultural assistance, and more.[vii] This spirit of volunteering is deeply rooted in our culture, and yet the level and magnitude of this era are astonishing.

These social needs are profound and persist and so are the volunteers. We continue to witness this spirit thriving in our society, and volunteering has not stopped for over 5 months. Coming to Israel during this time, one must find their place based on their abilities (physical and time) to get under the stretcher and lend a shoulder and hand.

Every year during Israel’s national holidays – Yom Ha’Shoa (Holocaust Remembrance Day), Yom Ha’Zikaron (Remembrance Day for the fallen soldiers and victims of terror), and Yom Ha’atzmaut (Independence Day), the soundtrack of Israel changes. This transformation is evident in every aspect of the public sphere. Israelis recognize it immediately, and it triggers a shift in both personal and collective moods. It is present on the radio – in the topics discussed and the music played, in newspapers and on TV. It is present in the streets on billboards and slogans posted around the country, and on cars in the form of flags and bumper stickers. It is present in social gatherings and the sites and places groups choose to visit and tour. And it is present in many more aspects of the culture surrounding us.

Similarly, the current period has its own unique soundtrack, different from what we are accustomed to. Coming to Israel and tuning into this distinct soundscape enables you to connect with Israelis on a different level. I make an effort to engage with the special TV shows and news segments, explore the posted poetry, discover new songs and reinterpretations of old ones tailored to this period. From street signs, billboards, and graffiti to special publications and articles—these are just a few elements I recommend tuning into.

Israel’s resilience rests on various foundations, and one crucial aspect is the ability to uphold a semblance of normality amid abnormal circumstances. In parts of the country, daily life and routines persist, even as others experience a state of war. I state this as a fact, without passing judgment. When visiting Israel, you can contribute to the country’s strength by engaging in everyday activities. Stroll down the street, sit in a coffee shop, attend a basketball or soccer game—activities that many Israelis are participating in, and ones I believe you should consider as well.

Traveling, touring, and hiking in Israel are the best ways to deepen your connection and commitment to the land, the people, our culture, and heritage. In a world where many challenge the right of Israel’s existence, by traveling the length and breadth of the country, Derech HaRaglayim – “Through the Feet,”[viii] you participate in ensuring its existence.

The economic state of Israel during war is challenging. We are a strong country and economy. Local small businesses have taken a toll, and your support can make a big difference. Just think about the tourist, hospitality, and restaurant businesses you support by simply arriving in Israel. Bring it all back with you. Share what you’ve experienced. Advocate for Israel. Sustain your enduring connections with Israel and its people, as well as the new ones you’ve forged during your trip. Your presence has made a statement—ensure to educate and transmit this sentiment to the next gen

[i] Chag; the verb L’Chug; to rejoice is also to circle, just like the meaning in Arabic Hadjj – the holiday of pilgrimage to Mecca. During the Jewish pilgrimage holidays, one would enter the temple in a circular manner, just as the Muslims circle the Kabba during their pilgrimage.

[ii] שָׁל֣וֹשׁ פְּעָמִ֣ים ׀ בַּשָּׁנָ֡ה יֵרָאֶ֨ה כָל־זְכוּרְךָ֜ אֶת־פְּנֵ֣י׀ יְהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֗יךָ בַּמָּקוֹם֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר יִבְחָ֔ר בְּחַ֧ג הַמַּצּ֛וֹת וּבְחַ֥ג הַשָּׁבֻע֖וֹת וּבְחַ֣ג הַסֻּכּ֑וֹת וְלֹ֧א יֵרָאֶ֛ה אֶת־פְּנֵ֥י יְהוָ֖ה רֵיקָֽם: (דברים פרק טז פסוק טז)

[iii] The place God dwells among his people. God is everywhere – this is due to our human needs.

[iv] Deuteronomy 15, 8-9: “If, however, there is a needy person among you, one of your kinsmen in any of your settlements in the land that the LORD your God is giving you, do not harden your heart and shut your hand against your needy kinsman .Rather, you must open your hand and lend him sufficient for whatever he needs.”

https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/372501-0 – the oldest known poor box, inscribed with the Hebrew word for “your brother” – “אחך”

[v] An historical account of this type of practice in the temple can be found in Mark 12, 41-44 (NIV)- The Widow’s Offering. “41 Jesus sat down opposite the place where the offerings were put and watched the crowd putting their money into the temple treasury. Many rich people threw in large amounts. 42 But a poor widow came and put in two very small copper coins, worth only a few cents.43 Calling his disciples to him, Jesus said, “Truly I tell you, this poor widow has put more into the treasury than all the others. 44 They all gave out of their wealth; but she, out of her poverty, put in everything—all she had to live on.”

[vi] See also:

Tractate Semachot 6:11 “These are they who must go round to the left: a mourner, an excommunicated person, one who has a sick person in his house, and one who lost an object. [When asked,] ‘Why do you go round to the left?’ [he answers,] ‘Because I am a mourner’. They reply, ‘May He Who dwells in this House comfort you’. [If he says,] ‘Because I am under a ban’, [they reply,] ‘May He Who dwells in this House put it into their heart to draw you near’; so said R. Meir. R. Jose said to him, ‘You make out as if they [who banned] passed a wrong judgment on him; but [what they say is,] “May He Who dwells in this house put it into your heart to hearken to the words of your colleagues so that they may draw you near” ’. To one who has a sick person in his house they say, ‘May He Who dwells in this House have mercy upon him’; and if he is barely living27lit. ‘son of existence’, far gone in his illness. [they say,] ‘May He have mercy upon him immediately’. It is related of a certain woman whose daughter was ill that she ascended the Temple Mount and went round it, and did not move from there until they came and told her, ‘She is cured’.

To one who lost some object they say, ‘May He Who dwells in this House put it into the heart of the finder to return it to you at once’. It is related of Eleazar b. Ḥananiah b. Hezekiah b. Gorion that he lost a scroll of the Torah which he had bought for one hundred minas. He ascended [the Temple Mount], went round it and did not move from there until they came and told him, ‘The scroll of the Torah has been found’.”

Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer 17:15: “Solomon saw that the observance of loving-kindness was great before the Holy One, blessed be He. When he built the Temple he erected two gates, one for the bridegrooms, and the other for the mourners and the excommunicated. On Sabbaths the Israelites went and sat between those two gates; and they knew that anyone who entered through the gate of the bridegrooms was a bridegroom, and they said to him, May He who dwells in this house cause thee to rejoice with sons and daughters. If one entered through the gate of the mourners with his upper lip covered, then they knew that he was a mourner, and they would say to him. May He who dwells || in this house comfort thee. If one entered through the gate of the mourners without having his upper lip covered, then they knew that he was excommunicated, and they would say to him, May He who dwells in this house put into thy heart (the desire) to listen to the words of thy associates, and may He put into the hearts of thy associates that they may draw thee near (to themselves), so that all Israel may discharge their duty by rendering the service of loving-kindness.”

[vii]Some websites of volunteering organization (amongst many others) https://www.levechad.org/?lang=en, https://www.leket.org/en/, https://eng.hashomer.org.il/, https://www.sar-el.org/programs/, https://www.hamal.org.il/