“We are reaching the final stretch of our capital campaign, having successfully secured the funds required for the renovation of our synagogue. I want to express my deep appreciation for your involvement in the planning committee. Together, you will be responsible for establishing the architectural and interior design guidelines. Your choices will significantly influence how our synagogue will be presented to the next generation of our community. Considering our budget constraints, it is imperative that we focus on the essentials and exercise prudence in our decision-making. While our ambitions are lofty, it is essential that we stay grounded in our approach. Thank you for your unwavering commitment, and we eagerly await your recommendations, confident that they will play a vital role in bringing our vision for the synagogue to life.”

Before entering one of the numerous ancient synagogues that have undergone excavation, renovation, restoration, and been made accessible to the public, I often share this scenario with various groups. These synagogues are significant both in terms of their historical importance and their aesthetic appeal, attracting researchers and visitors from all walks of life. For nearly two thousand years, synagogues have stood at the heart of organized Jewish communities worldwide. Many Jews have had the opportunity to visit a synagogue, with some doing so regularly and others more sporadically.

As we traverse the globe, a visit to a local synagogue is frequently included in our itinerary as a means of exploring and delving into the rich history of Jewish life in that particular region. On occasion, we attend services at an active local synagogue, affording us the chance to connect with members of the current local community. Sometimes, a visit to the local synagogue may simply serve as an opportunity to nourish one’s Jewish identity and conscience. What remains paramount is that when I present this challenge, most individuals possess a general understanding of what is expected in a synagogue or its sacred sanctuary.

I allow the group a few moments for contemplation and discussion amongst themselves before turning to them and posing the question: “So, what is our vision for this synagogue? What have you collectively decided to include?” Typically, the initial responses encompass the fundamental elements that define any synagogue: an Aron HaKodesh (Ark for the Torah), Torah Scrolls, Siddurim (prayer books), a Bima (pulpit for the Shaliach Tzibor), where the cantor leads prayers, and the Torah is read. The responses also include the Ner Tamid (eternal lamp) and, of course, the plaques—dedications that honor and remember the founders, members, and donors of our community.

As we delve further into the conversation and explore the design and decorative aspects of the interior, the discussion becomes more complex. We consider elements such as symbols, artwork, language, biblical and rabbinic verses, and quotes, among other aspects. Often, the very first symbol mentioned is the Magen David, commonly known as the Jewish Star. Despite its widespread use today, it is a relatively modern Jewish symbol. We then engage in a back-and-forth discussion about various Jewish symbols and reach a consensus that the Menorah, the seven-branched golden oil candelabra that once stood in the temple, holds the distinction of being the most enduring and widely used Jewish symbol since antiquity.

Interestingly, a distinguishing feature of many archaeological sites in the land of Israel, differentiating a synagogue from a church in the Byzantine Basilica style, is the presence of an ornamental architectural object bearing the image of a Menorah. Its sight evokes an immediate recognition and elicits smiles from those who see it, as it serves as a timeless symbol of the Jewish faith.

Upon stepping into the ancient synagogue, a wave of astonishment, amazement, and sheer awe washes over us as we are captivated by the exquisite beauty of the structure. Following my historical and archaeological insights, we find a moment to contemplate the parallels and distinctions between the magnificent scene before us, the ornamentation they are familiar with in their home synagogues or have encountered while visiting other synagogues worldwide, and the ideas they had proposed for “their” synagogue only a short while ago as we sat outside in the shade.

One aspect that never fails to bring smiles to the faces of most groups is the inscriptions bearing names within the synagogue. It’s not just the names themselves, whether they are familiar Jewish names or not, that capture their attention. What truly piques their interest and elicits those smiles is the content of these inscriptions. Often, these inscriptions are dedications that recognize the community members who contributed to the construction, adornment, and upkeep of the synagogue. This resonates with them because in our own communities, we similarly honor those who have played a role in building and sustaining our communal spaces, whether through financial contributions or other forms of commitment and support.

As we explore the similarities and differences between the ancient synagogue we’re standing in and the synagogues we know from back home, numerous questions emerge. We ponder the historical role of the synagogue compared to its present-day function. We scrutinize the physical layout of the synagogue, its furnishings, and the artwork. We delve into inquiries such as when Jewish art began to incorporate depictions of humans and animals, and the origins of the symbols we use. At some of the ancient synagogues in Israel, we encounter mosaics featuring zodiac signs and even Helios, the ancient Greek sun god at their core. This can lead to comments like, “Is that a Jewish symbol?” Additionally, we come across symbols from the Jerusalem Temple, as well as depictions of natural flora, fauna, and animals. This often leads to the question of whether such depictions are permissible in Jewish tradition.

We grapple with profound inquiries, such as the essence of Jewish symbols and what is deemed appropriate for display in our sacred and holy communal spaces. We contemplate the extent to which external influences are permitted, and if they are, whether they are incorporated as-is or undergo a process of adaptation, a “Judefication” if you will. This entails assigning new meanings, reinterpreting, or employing them in their original form.

If we were to pose a more general question, it might read as follows: What values do we, as the Jewish people, consider uniquely our own, reflective of our Jewish identity? How do we manifest and exhibit these values within our public sphere? Moreover, we ponder what values and symbols we may have relinquished over time and which elements we regard as foreign to our Jewish cultural heritage. We consider the degree to which external influences are assimilated into our culture and in what manner. What aspects do we reject and perceive as foreign, and which ones do we embrace through a process of conversion, while identifying boundaries of acceptability?

Years ago, the synagogue in my community found its home in an impermanent structure, to be more specific, two mobile caravans that were merged and refurbished to create a place of worship for the community. For an extended period, this served as the gathering place for community members who convened three times a day for traditional Jewish prayers, and on Shabbat and Jewish holidays, the numbers swelled. It took many years for the community to expand and accumulate enough resources to construct the magnificent synagogue that now proudly stands at the heart of our community. During our tenure in the temporary building, renovations were necessary, and the construction project was entrusted to a skilled and inventive member of the community.

The walls received a fresh coat of paint, the flooring was reinforced, and a new wooden door adorned with a Star of David replaced the old, creaking one that barely closed. A new set of stairs leading up to the synagogue was installed, complete with exquisite metalwork to serve as handrails, providing additional convenience and beauty. The person overseeing the renovations went the extra mile to offer the community added comfort and aesthetics. Among the thoughtful touches, they ventured to the old city market in Jerusalem to obtain a couple of tiles featuring beautiful paintings that seamlessly blended with the new pavement in front of the synagogue.

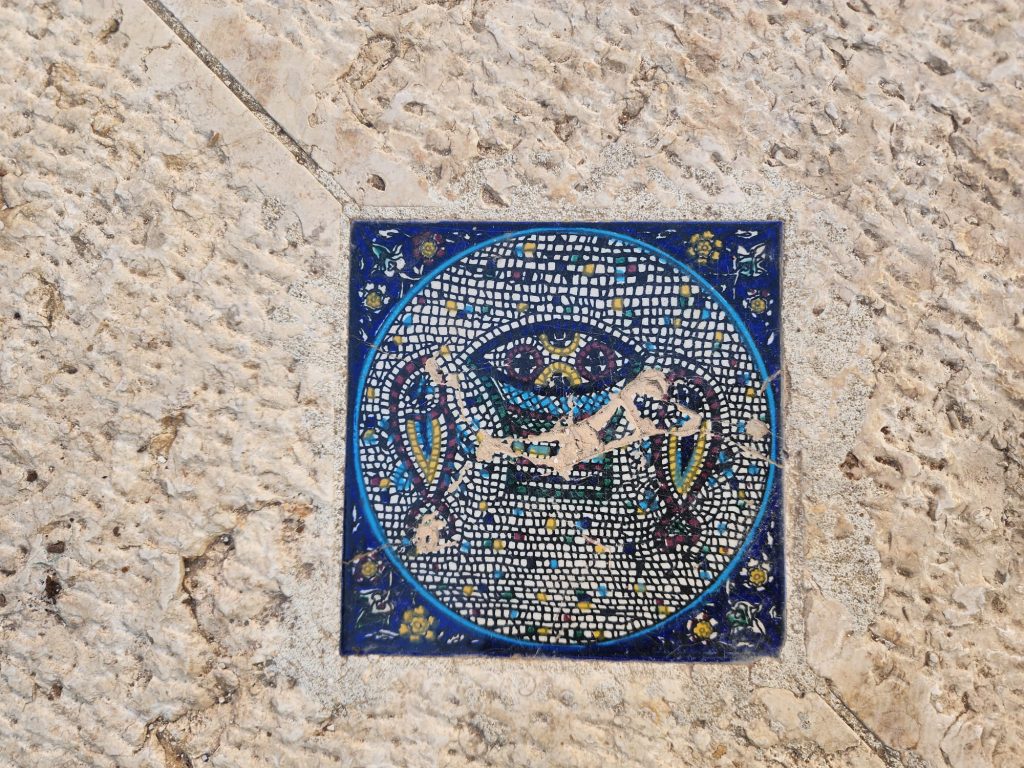

As a result, when the synagogue doors were opened, and congregants ascended the stairs, they trod upon a floor adorned with striking pictures embedded in the stonework. It was during this time that I found myself contemplating the appropriateness of every symbol. Just a few steps from the synagogue’s entrance, integrated into the stonework, was a ceramic depiction of the mosaic floor from the Church of Tabgha on the Sea of Galilee, also known as the Church of the Multiplication. The image portrayed a basket with loaves of bread and two fish, one on each side, depicting one of the most pivotal scenes in the New Testament, recounted in all four Gospels—the miraculous feeding of the multitude by Jesus.

This event holds significant importance, both in its physical manifestation as Jesus providing for 5000 people and its metaphorical significance in symbolizing the provision of essential spiritual sustenance. It struck me as rather remarkable that this Christian symbol graced the ground just steps away from the entrance to my Jewish community synagogue. I recognize that it was not intentionally placed there; it was a mere happenstance. A community member had procured these decorative images, thinking they would be a nice addition. Nevertheless, I couldn’t help but wonder why, among all the symbols and representations in the world, this Jewish synagogue had inadvertently welcomed one of the most important Christian symbols.

It occurred once more, this time as I spent a Shabbat in the dormitories of a religious Jewish girls’ high school that had been rented out for a family Simcha, a joyous celebration, during one of the weekends when the girls were away. I recall entering the on-campus synagogue for Friday night services, Kabbalat Shabbat. My usual practice is to survey the surroundings to gain some insight into my location. I like to peruse the books on the shelf, as it provides a glimpse of the subjects studied within these walls. During this exploration, I made a discovery that left me intrigued.

On the wall, there hung a frame containing three images related to the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. The first portrayed an ancient coin, the second depicted the second temple in its grandeur before its eventual destruction on Tisha B’Av in the year 70 CE, and the third displayed the scapegoat sent out into the desert with a red string around its head by the high priest during the Yom Kippur service. Collectively, these images formed a captivating triptych representing the Temple of Jerusalem and the atonement rituals conducted there.

What struck me was the absence of any commentary beneath each image, providing information about their origins. In other words, there was no credit given to the pictures. While most of those who frequent the synagogue are likely to associate these images with the temple and its rituals, I wondered whether they could provide the specific context for each picture. Who created them? When? Where? And for what purpose?

In my role as a guide and someone deeply interested in this subject, I readily recognized the pictures and their origins. It struck me that even a brief descriptive sentence placed below each image could significantly enhance understanding and spare individuals from potential embarrassment due to a lack of information.[1]

For the first picture, the title could read, “Coin from the Period of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, 123-125 CE.” This coin features a depiction of a structure with two columns on either side, suggesting a resemblance to the Jachin and Boaz pillars that stood at the entrance of the Temple in Jerusalem. Within this structure lies a representation that scholars have debated: some believe it to be the Showbread table, one of the three elements found inside the Holy, the initial section of the temple. Others contend that it represents the Holy of Holies, featuring the Ark of the Covenant, which resided there during the first temple period but was absent during the era of the second temple. This coin symbolizes the Bar Kokhba Revolt’s goal of restoring Jewish sovereignty in Israel by rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem to the grandeur of Solomon’s first temple, with the Ark of the Covenant at its center.

As for the second picture, it would merit the description, “The Second Temple in Jerusalem, based on the reconstruction/artwork of Professor [Name].” This image portrays the Temple in Jerusalem during its prime years leading up to its destruction in 70 CE. This particular temple was extensively renovated and expanded by King Herod during the latter part of the first century BCE. It earned a reputation as one of the most magnificent structures constructed during the Roman period. Our sages have praised this temple, stating, “One who has not seen Herod’s building has never seen a beautiful building in his life.”[2] Numerous remains in the vicinity of this extensive complex have been excavated and unveiled over the years, with ongoing excavations bringing more to light each day. These sites draw visitors from all over and have prompted various reconstructions of the temple, hence the need for a clear attribution to a specific reconstruction.

The third picture stands out as the most intriguing. It features a robust, full-of-life scapegoat with a red string around its horns, standing on the shores of the Dead Sea. Jewish sources tell us that on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, the scapegoat was taken out to the desert and then pushed down the mountain to the east, leading to the Dead Sea, where it would meet its demise. The Mishnah records that by the time the goat was halfway down the mountain, it was already in pieces. In the temple, this atonement would be signified by the other strip of red string left behind turning white.[3]

Given my knowledge of these images, I would propose a title that reads, “The Scapegoat: by William Holman Hunt, 1854-1855.” Had proper research and credits been provided, individuals would likely understand that the artist of this painting, William Holman Hunt, was a devout Christian who resided in Jerusalem during the nineteenth century. The scapegoat he depicted in his artwork symbolizes Jesus Christ after his resurrection. During the temple period, a scapegoat would not have been found alive in the desert on the shores of the Dead Sea. Thus, the image represents Jesus, who endured and continues to suffer after his resurrection. Had this research been conducted beforehand, this painting likely would not have been included in this Temple triptych and would not hang within an Orthodox Jewish synagogue. The Jewish faith has traditionally rejected Jesus Christ as the Messiah and Savior, who, according to Christian belief, resurrected after crucifixion.

These two instances, along with numerous others, prompt the important question of what is deemed appropriate to assimilate into our cultural and traditional fabric and what should be rejected. I do not believe that these critical oversights were intentional; quite the opposite, I attribute them to ignorance and perhaps a degree of negligence. We cannot reasonably expect everyone to possess comprehensive knowledge of every facet, but what we can and should anticipate is the act of giving credit, as advised by the Rabbis: “Whoever reports a saying in the name of the one who said it brings redemption to the world.” Offering credit serves not only to acknowledge and honor those from whom we’ve learned but also to provide us with a deeper understanding of the context, background, and values associated with each element of our shared narrative.

In a time when discussions of identity politics have garnered a negative connotation, with some viewing particular identities as divisive, I believe these questions remain immensely relevant. While we must fortify our universal values, it is equally important to delve into a better understanding of our individual identities. The more we comprehend who we are, the more we appreciate our distinct cultural heritage. I hold that this recognition should naturally lead to greater respect for the particular identities of others. In today’s ever-changing global landscape, I firmly believe that the study of humanities, history, philosophy, and Torah is more vital than ever to guide us through these complex and evolving dynamics.

[1] B. Talmud, Megillah 15A. “And Rabbi Elazar further said that Rabbi Ḥanina said: Whoever reports a saying in the name of he who said it brings redemption to the world. As it is stated with respect to the incident of Bigthan and Teresh: “And Esther reported it to the king in the name of Mordecai” (Esther 2:22).”

[2] B. Talmud, Bava Batra 4a; Sukkah 51b.

[3] Mishna Yoma 6, 6. “He divided a strip of crimson into two parts, half of the strip tied to the rock, and half of it tied between the two horns of the goat. And he pushed the goat backward, and it rolls and descends. And it would not reach halfway down the mountain until it was torn limb from limb.”

Mishna Yoma 6, 8. Rabbi Yishmael says: … There was a strip of crimson tied to the entrance to the Sanctuary, and when the goat reached the wilderness and the mitzva was fulfilled the strip would turn white, as it is stated: “Though your sins be as scarlet, they will become white as snow” (Isaiah 1:18).