In my role as a Guide and Educator in Israel, I regularly encounter diverse groups of people. The initial phase of any trip involves engaging in casual conversations to establish a personal connection. This process fosters intimacy and rapport, cultivating a trust that I, as their guide, truly comprehend their preferences and will cater to their pace and interests. I find great joy in these introductory conversations as they allow me to delve into the unique stories and backgrounds of the individuals I am guiding. I am open to sharing aspects of my own life, and the real satisfaction lies in building strong connections with those I assist. Although establishing this personal touch is more seamless in smaller groups, such as during individual tours, it becomes a more intricate challenge when dealing with larger groups, like a bus full of 50 people.

One of the initial inquiries I always pose to the group, regardless of its size, is, “Have you been to Israel before?” Welcoming first-time visitors is consistently invigorating; their excitement mirrors my own. I make it a point to acknowledge them collectively and individually throughout the journey, not only on an intellectual level but also on an emotional one. On the other hand, there are those who are familiar with Israel, some being frequent travelers having explored the country multiple times. They are well-acquainted with major tourist sites, have preferred restaurants and shops, and may even have friends or family in the region. It’s enriching to tap into their knowledge and previous experiences, fostering a deeper connection to Israel and heightening the anticipation for first-time visitors.

Then, there are individuals who have visited Israel once or only briefly. The subsequent essential query revolves around the timing of their last visit. Given the rapid changes in Israel over the past couple of decades, those whose last visit was more than a decade ago may find the current landscape almost unrecognizable, and they are going to experience it almost like for the first time.

I use the term “almost” because these individuals still retain memories and emotions from their past experiences here. This typically leads to what I’ve come to call ‘The Parade of Nostalgia.’ Interestingly, it isn’t prompted by any specific question I pose; rather, it unfolds organically. Beginning in the group setting, it transitions into individual conversations with me. You’ll hear statements like, “I was here with my family for my Bar Mitzvah in the 60s,” or “During my college years right after the Yom Kippur War, I spent time on a Kibbutz,” or “In the mid-80s, I had a semester at Hebrew University on Mount Scopus.” These declarations are accompanied by personal stories, shared with smiles and glistening eyes. This parade of nostalgia persists throughout the entire trip. Every so often, someone will remark, “I remember being here,” or express disbelief, saying, “It wasn’t like this the last time.” Without fail, there’s always that one person who, at every destination, pauses to share a personal story or connection to the site we’re visiting. We all anticipate it, and yet, it manages to surprise us each time.

During one-on-one interactions, those brimming with nostalgia often seize the opportunity to engage with me, sharing personal anecdotes. Whether at the front of the bus during lengthy rides, amid walks and hikes between guiding points, or any other available free time, they seek moments to connect. These conversations frequently include queries about the current existence of particular sites, whether I’m acquainted with their previous tour guide, or if I know a specific individual they encountered on prior trips. Oftentimes, these discussions are complemented by the unveiling of photographs capturing moments from these experiences or showcasing souvenirs they brought back—a piece of jewelry, a T-shirt, or any other memento reminiscent of their time exploring Israel.

Not just once, but on several occasions during these casual personal conversations, individuals have taken out a small bag containing Israeli currency from their pockets. By currency, I’m referring to banknotes and coins issued by the State of Israel. Typically, these occurrences unfold on the initial day of the trip, right as we reach the hotel. People are gathering their luggage and waiting to check in. I believe this timing is attributed to the fact that, during our first journey together, I often address crucial aspects of the trip. These include discussions about the weather forecast, suitable attire for various sites, information about food and beverages, and insights on currency matters. This comprehensive discussion covers topics such as where and how to exchange money, acceptable forms of payment with different vendors, tips and expressions of gratitude, and other pertinent financial considerations. It seems that everyone likes to talk about money.

Following the show comes the tell and the questions. They inquire, “I’ve held onto these notes since my last visit to Israel. Can you let me know their current value? Are they still valid for use?” Alternatively, someone might share, “My parents or grandparents gave me these before my journey to Israel. They’ve kept them since their own visit. Can you determine their value, and can they still be used?” Handling contemporary currency is straightforward – you assess its value and guide them accordingly. However, it becomes more intricate when conveying that the currency they possess is no longer in circulation, holds minimal monetary value, and is practically obsolete.

Once they understand this reality, the inevitable question arises: what should they do with the outdated currency? I present two options: firstly, they can hold onto it until the trip concludes. Secondly, if they have no use for it, I offer to take it off their hands. This latter option, however, poses a dilemma for me, as I genuinely appreciate collecting Israeli currency. Over the years, I’ve amassed a significant collection that I incorporate into my tours for display and discussion. Each Israeli coin and banknote serves as a window into Israeli society, providing insights into the specific period of issuance. We’ll delve into this aspect later. However, informing participants that I’ll discuss the banknotes throughout the trip significantly reduces the likelihood of receiving them back at the trip’s conclusion.

Years ago, I devised an Israeli banknote quiz to entertain during lengthy bus rides, blending my two passions: educating about Israel and fostering enjoyable group experiences. I encourage people to take out their Israeli notes, assuring them there’s no intention to take their money. Additionally, I distribute imitation banknotes sourced from a kindergarten store. These replicas feature identical artwork to official banknotes but are printed on inexpensive, smaller-sized paper, resembling monopoly money yet mirroring the current Israeli currency in circulation.

Admittedly, this approach has led to a few complications. Once, an irate gas station owner pursued our bus during a 10-minute pit stop. A child, unaware the money was fake, used it to buy a can of cola and returned to the bus not only with the beverage but also with legitimate change for the fake 50 shekel banknote. As the commotion subsided, the owner realized what had occurred and dashed out of the store in pursuit of the bus. It was quite a scene, one I hope never repeats, but it hasn’t deterred me from continuing to use my quiz.

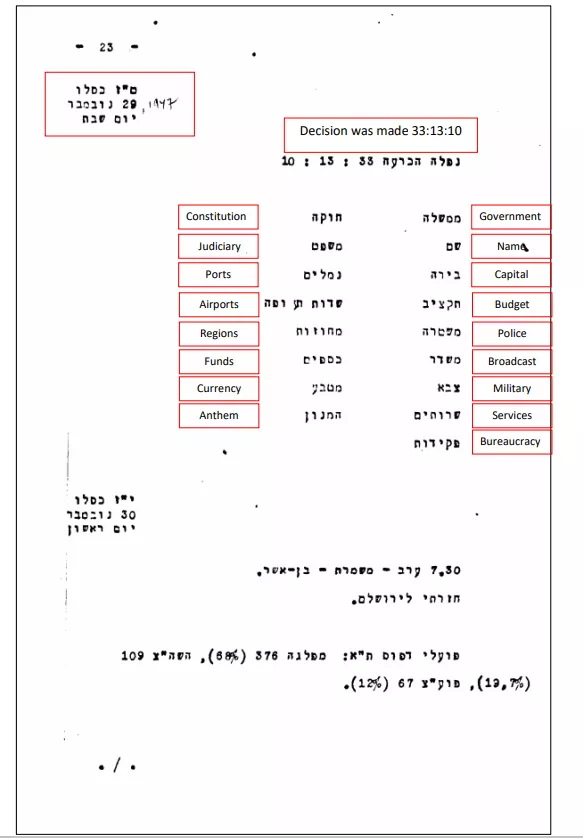

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 181, which proposed the partition of the British-Ruled Palestine Mandate into a Jewish State and an Arab state. The resolution passed with 33 in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. Following this pivotal decision, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish agency and de facto leader of the Yishuv (Jewish residents in the land of Israel during Ottoman rule and Mandatory Palestine), made an entry in his diary.

At the top of the page, he noted, “Decision was made 33:13:10,” which was followed by a two-column list outlining various aspects, effectively Ben-Gurion’s ‘to-do list.’ The columns included items such as Government, Name, Capital, Budget, Police, Broadcast, Military, Services, Bureaucracy, Constitution, Law, Ports, Airport, Districts and Regions, Funds, Currency, and Anthem. This comprehensive list reflected Ben-Gurion’s visionary outlook combined with a pragmatic and realistic approach. He understood the imminent threat of war and recognized that the nascent State required attention to every aspect outlined in his meticulous list.

Ensuring the emergence of a functioning state required not only an existential necessity but also a strategic power statement and symbol of sovereignty. Recognizing this imperative, the Jewish leadership in Palestine realized the importance of establishing an organization to assume control of the ‘Mandatory Currency Board’ and possess the authority to issue banknotes (money). The natural choice for this role was The Anglo-Palestine Bank, owned by the World Zionist Organization (WZO) and the largest bank in the Yishuv at that time.[i]

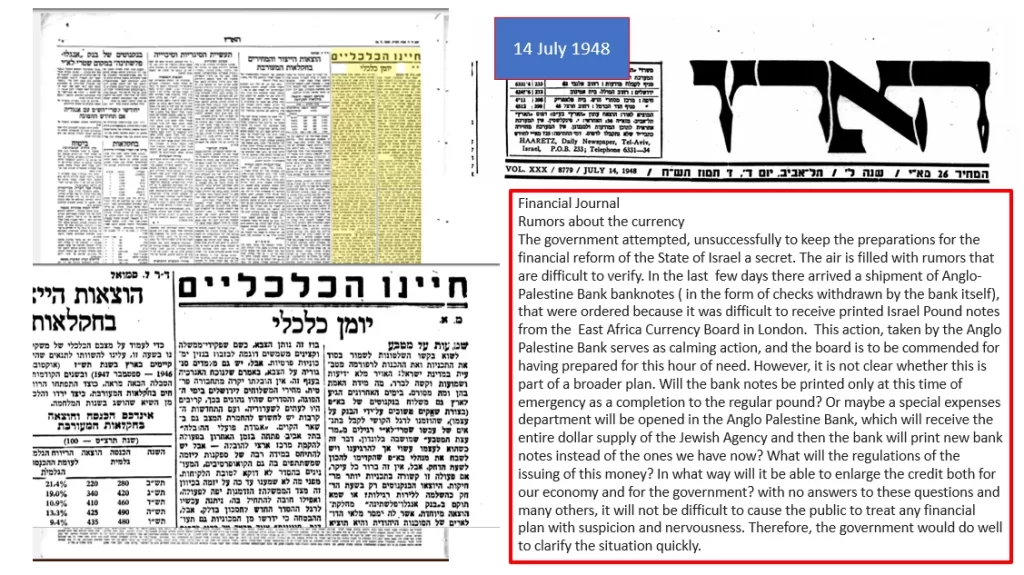

In response to the escalating urgency, the bank’s CEO, E.S. Hoffien, spent a significant portion of the early months of 1948 in the United States, seeking a resolution to the impending crisis. The situation intensified towards the end of February when the British Government declared the removal of Palestine from the sterling area. They issued a warning that, starting from May 1st, the ‘Mandatory Currency Board’ would no longer be able to supply banknotes and currency in Palestine.

Hoffien engaged in negotiations with the president of the American Bank Note Company, a company known for printing currency for various nations. The discussions proved challenging given that Israel had not yet attained statehood, and the concept of a bank issuing currency was unprecedented. Questions arose regarding the legal framework under which the currency would be printed. Additionally, obtaining approval from the State Department was essential for printing currency for a foreign state, a prospect hindered by the department’s opposition to the creation of the State of Israel at that time.

A compromise was eventually reached: the legal status would not be printed on the bills within the United States; instead, it would be added upon their arrival in the Land of Israel. The entity responsible for issuing the currency would be The Anglo-Palestine Bank, and its name would be displayed in Hebrew, Arabic, and English. The artistic design was borrowed from Chinese banknotes, and the signatures of the two bank heads, Hoffien and Barnet, were added. On April 19, 1948, less than four weeks before the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel, the printing machines at the American Bank Note Company commenced the production of the currency.

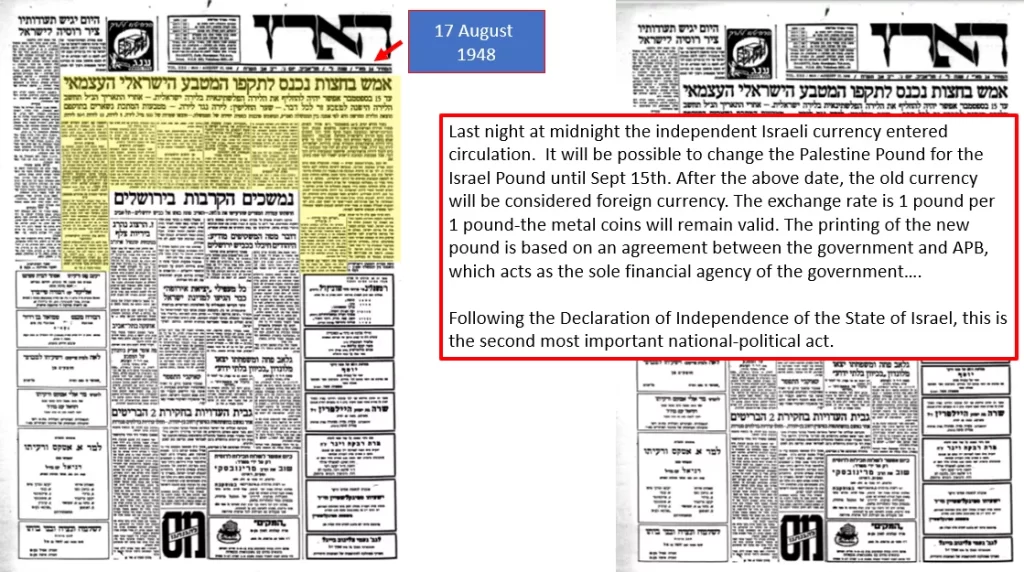

The transportation of the banknotes to the land of Israel became a significant challenge, only resolved in June. The Government of the State of Israel leased a Dutch KLM plane, primarily used to repatriate to the US the body of Colonel Mickey Marcus, to fly the money back to the US. Two IDF major-generals, Moshe Dayan and Yossi Harel, accompanied the flight and utilized the plane to transport the currency to Israel. The plane was so heavily laden that the remaining escorts couldn’t return with them. The landing took place near kibbutz Ein Shemer, as Lod was still under Arab control. Rumors regarding the currency circulated in Israeli newspapers.

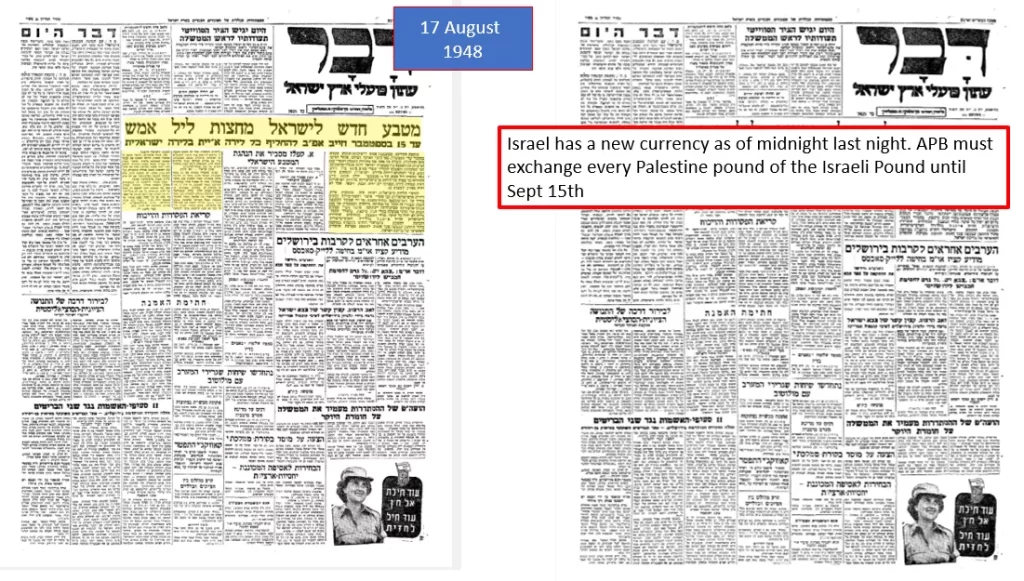

On Tuesday, August 18, 1948, a holiday for the young emerging state, the provisional government gathered and unanimously approved the agreement between the State and the Anglo-Palestine Bank to issue a new Israeli currency. David Ben-Gurion declared, “Today we cut off our connection to a monetary system of a foreign government.” The Haaretz newspaper reported the following morning, “After the Declaration of Independence of the State of Israel, this is the second political act in its importance.” The next day, all citizens of the State of Israel were urged to exchange their old Mandatory currency for the new Israeli one, resulting in long lines at banks. Following the custom of those days, the phrase “After Two Thousand Years” echoed across the country, with many reciting the Shehechiyanu blessing.

The introduction of the new banknotes was generally embraced by the press, although some criticisms arose regarding their design and the absence of the State’s name. Certain objections were raised about the space allocated to English and Arabic languages. The primary concern, however, centered around the fact that the currency retained the name “Palestine pound,” creating the impression that the State of Israel did not exist. The first Israeli currency was only minted in October 1948. The banknotes issued by the Anglo-Palestine Bank continued in circulation until June 1952. Subsequently, with the establishment of Bank Leumi, new banknotes were introduced on its behalf. Notably, for the first time, the Palestine pound was replaced by the Israeli pound. On December 1, 1954, the Bank of Israel was founded, and one of its initial actions was to issue new banknotes. These were distributed on August 4, 1955, bearing the name of the central bank.

Upon the establishment of a national currency, the responsibility for designing and minting coins, as well as printing banknotes, was entrusted to the ‘Bank of Israel.’ Over the past 75 years, new series of currency have been introduced frequently. This frequent issuance is driven by various factors, including the need for additional currency, enhancing security measures against fraud and counterfeiting, managing inflation, and responding to currency changes (such as transitioning from the lira to the Shekel, and subsequently from the Shekel to the New Israel Shekel). With each issuance of a new currency series, the Bank of Israel introduces fresh designs.

Currency has long served as the primary means of facilitating the exchange of goods and services, essentially driving trade. Beyond its economic role, currency has functioned as a form of social media, acting as the swiftest means to disseminate information across vast distances in minimal time. It has also been a tool for showcasing power and authority, with the change of empires often coinciding with alterations in currency. Transitions in rulers were marked by shifts in currency, where the type of currency, its artwork, language, and inscriptions were deliberately employed to convey specific messages. Let’s explore a couple of coins that were minted during the Roman rule over the land of Israel.

Amidst the Great Jewish Revolt against the Romans in Judea from 66-73 CE, which culminated in the destruction of the Jewish Temple in 70 CE, the leadership of the Jewish rebels engaged in the minting of coins. These coins served a dual purpose—they weren’t merely tokens of monetary value but functioned as a potent propaganda tool. Their aim was to influence public opinion, garnering support for the continuation of the revolt even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. The act of minting itself constituted an act of rebellion, as coin minting was a privilege reserved for authorities. Rigorous oversight was imposed on this matter, accompanied by severe penalties for those who violated this established law.[ii]

Over the span of four years, from the inception of the revolt until the Temple’s destruction, coins were minted by the leadership of the Jewish rebels. The silver coins included three denominations: the shekel, half-shekel, and quarter-shekel. In contrast, the bronze coins were less abundant and featured initial low values like the Prutah, progressing to include some higher denominations.

These coins were meticulously designed, bearing distinctive and easily recognizable Jewish symbols that held profound meaning for the people of that era. Notable symbols included a goblet representing a temple vessel, grape leaves and amphoras symbolizing wine, a staff adorned with three young pomegranates signifying prosperity and abundance, and, on later coins, the Arba’at Ha’Minim—the four species used during Chag Sukkot, symbolizing unity amongst the people.

Inscribed in ancient Hebrew script reminiscent of the First Temple period rather than the contemporary script, the coins conveyed a sense of nostalgia for better times. The inscriptions featured phrases such as “Shekel Yisrael” (Shekel of Israel), “Yerushalyim Hakdosha” (Holy Jerusalem), “Herut Zion” (Freedom of Zion), and, on later coins, “LeGeulat Zion” (For the Redemption of Zion). Additionally, the inscriptions indicated the year of minting, counting from the revolt’s commencement: Year One, Year Two, Year Three, Year Four, and, in very few instances, Year Five until the Temple’s destruction.

By incorporating symbols and inscriptions on the coins that vividly conveyed religious, cultural, and national ideas and perceptions, the leadership strategically positioned them at the forefront of attention and collective consciousness.

This approach was subsequently employed post-70 CE through a series of commemorative coins initially issued by Roman Emperor Vespasian to commemorate the conquest of Judea and the destruction of the Jewish Temple by his son Titus. Spanning over 25 years, these coins were minted under Vespasian and his two succeeding sons who ascended to the throne. Struck in bronze, silver, and gold by mints across the Roman Empire, including Judea itself, they covered various denominations and became known as the Judaea Capta coinage, bearing the inscription proclaiming the conquest of Judea.

Featuring Judaea as a seated female in an attitude of mourning beside a palm tree, with a standing figure representing the Roman Emperor or the goddess Victoria to the left, these coins circulated widely throughout the Roman Empire. Termed a common coin, it swiftly conveyed a clear message, glorifying the emperor with his titles and proudly displaying his triumphs.

Following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and the subsequent loss of Jewish independence and sovereignty, the absence of Jewish coin minting persisted until the establishment of the State of Israel. However, during the outbreak of the ‘second revolt’ against the Romans, known as the Bar Kochva rebellion in 132 CE, a remarkable occurrence unfolded with the appearance of new independent coins. These coins were ingeniously crafted by utilizing pre-existing Roman coins, which were collected, meticulously sanded down to obscure the existing figures, and then re-struck.

Adorned with symbols of profound religious significance, these coins featured depictions such as the facade of a building, likely representing the Temple and symbolizing the collective aspirations to rebuild it from its ruins. Musical instruments, including the harp, violin, and two trumpets used in the Temple, were also prominently displayed. Furthermore, representations of the Arba’at Ha’Minim (the four species), grapevines, and dates were incorporated. The coins bore inscriptions with the names of the rebellion leaders—Shimon Nasi Yisrael and Elazar HaChoen—and prominently highlighted the name Jerusalem.

Revisiting the strategic use of coins as a tool of propaganda, this episode echoed the events 60 years earlier during the first revolt. The intentional blurring of Roman symbols served as a symbolic awakening, signaling a rejection of Roman culture and the resurgence of Jewish culture. This resurgence was marked by a profound messianic expectation and a fervent anticipation of the Temple’s restoration.

The Roman response was swift. The rebellion faced suppression by the Roman legions under Emperor Hadrian, resulting in a devastating loss of life, with historians estimating casualties in the hundreds of thousands. Numerous settlements in the region were razed, leaving Judea nearly desolate. The Jewish focal point shifted to the Galilee, and a considerable number of Jews migrated to Babylon. Hadrian, in a symbolic move, changed the name of the province of Judea to “Syria-Palastina,” and upon the ruins of Jerusalem, the pagan city “Aelia Capitolina” was erected in homage to Emperor Hadrian and the god Jupiter Capitolinus.

Under Hadrian’s reign, the construction of Aelia Capitolina City coins began in 130 CE, portraying the emperor’s profile on the obverse and featuring the ceremony of circumductio on the reverse. This ceremony symbolized the founding of the city as a colony, depicting the emperor ploughing the first furrow of the city limits with an ox and cow. Over a span of 15 emperors, “Aelia Capitolina” coins were minted in Jerusalem, showcasing various symbols representing Roman culture and inscriptions in Latin. Beyond serving the practical need for currency, these coins undoubtedly served a higher purpose by signaling the dominance of specific powers and cultures in the region.

The Jewish coins minted during the rebellions against the Romans served as a public expression and a beacon of hope, reflecting the yearning for religious, cultural, and national sovereignty. This significance is carried forward to the establishment of the modern State of Israel, where the inspiration for new coins drew from ancient counterparts. Symbols and images from antiquity were repurposed, establishing a symbolic link between contemporary national aspirations and historical longings.

This brings us to the modern designs of coins and banknotes in the State of Israel. Since its establishment, the country has issued over 60 different banknotes. Initially, the artwork was confined to graphic designs, but over time, idealistic figures and personalities were introduced and have consistently appeared in all series, including the current banknotes in circulation. The State of Israel has effectively utilized this medium, incorporating symbols into everyday circulation, to convey messages. A meticulous examination of the symbolic artwork on the banknotes, alongside the historical context of their issuance, provides insights into the prevailing ideologies of the time.

The inaugural series featuring Israeli artwork was introduced in 1955 as the Israel Pound Series A (Alef). A committee, overseen by the first Governor of the Bank of Israel, David Horowitz, selected the designs, crafted by artists from the De La Rue currency print shop in London. This series, known as the Landscape series, prominently featured a distinctive landscape from Israel on the front side of each bill, accompanied by abstracted paintings on the back.

The bills showcased various landscapes, with the 500 Pruta (1000th part of the Israeli pound) displaying the remains of the Ancient Synagogue in Baram. The 1 Lira (Pound) highlighted the landscape of the Upper Galilee, while the 5 Lira (Pound) depicted the Negev desert with a settlement and equipment for tillage. The 10 Lira (Pound) featured the landscape of the Emek (valley), specifically the Jezreel Valley, with local settlements and cultivated fields. Lastly, the 50 Lira (Pound) exhibited the landscape of the road ascending to Jerusalem.

In response to public dissatisfaction with the abstract paintings on the bills, the Governor of the Bank opted for a new series. The Israel Pound Series B (Bet) entered circulation between 1959-1960, marking the first series to feature idealistic characters rather than known figures. To determine the artistic direction, a public committee was established, shaping the character of the artwork on the bills.

The ½ Lira (Pound) bill depicted a female member of the Nahal, an army unit combining military service and the establishment of agricultural settlements, holding a basket of oranges against a backdrop of cultivated fields. The reverse side showcased an image of the archaeological site known as the Tombs of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem. The 1 Lira (Pound) bill portrayed a fisherman with fishing equipment against a bay background, while the reverse displayed a mosaic floor from the ancient synagogue in Ussefiya on Mount Carmel. The 5 Lira (Pound) bill featured a Hebrew worker with a hammer and a factory in the background, earning the nickname ‘The Builder’s Bill.’ On the reverse side was an image of the ancient Hebrew seal—a roaring lion found in Tel Megiddo. The 10 Lira (Pound) bill depicted a scientist in a laboratory, with the reverse side showcasing one of the Dead Sea Scrolls—the complete scroll of Isaiah discovered in Cave No. 1 in Qumran—alongside the pottery vessels they were found in. The 50 Lira (Pound) bill depicted two young pioneers, a female Yemenite and a male Ashkenazi, embodying Ben-Gurion’s vision of Kibbutz Galuyot (the ingathering of the exile), with an agricultural settlement in the Negev in the background. Known as ‘The Pioneer Bill,’ the reverse side displayed a mosaic from a synagogue in Nirim in the northern Negev, featuring the menorah, the Jewish historical symbol, a shofar, and lulav.

This series underscored two crucial values central to early Zionism and the State of Israel: the significance of work, labor, and self-sufficiency, particularly in connection with the esteemed Hebrew worker, and the value of archaeology as a bridge to the past, fostering a sense of rootedness and belonging. Each bill encapsulated both the past and the present, symbolizing the state’s efforts to bridge the gap between antiquity and the present, affirming the people’s rightful ownership of the land.[iii]

Once again, the public voiced dissatisfaction with the artwork, expressing discontent with the overly idealistic characters reminiscent of communist regimes.

In response, the Bank of Israel initiated its third series of Israel Pounds in 1969—Series C (Gemel). This marked a departure, as it became the first series to portray portraits of recognized personalities who significantly influenced the creation of the State of Israel—prominent Zionist and state leaders. Notably, this series was also the first to be designed by foreign designers, guided by provided information.

The inaugural note in this series was the 100 Lira (Pound), featuring the portrait of Theodor Herzl on the front, accompanied by the emblem of the State of Israel (Menorah and Olive Branches, encircled by symbols of the twelve tribes of Israel) on the reverse side. The 5 Lira (Pound) depicted the portrait of Albert Einstein on the front, while the back showcased the Soreq Nuclear Research Center, underscoring the importance of science in the nation’s progress. The 10 Lira (Pound) displayed the portrait of the National Poet, Haim Nahman Bialik, on the front, with the back featuring Bialik’s Tel Aviv home—a hub for cultural and literary gatherings. The 50 Lira (Pound) presented the portrait of Zionist leader and the first President of the State of Israel, Chaim Weizmann, on the front, with the back displaying the Knesset building (Israel’s parliament), dedicated on August 30, 1966, just two years before the note’s issuance.

While the individuals featured on the banknotes were renowned, it became evident that not everyone recognized or knew them. Consequently, their names were later added in writing, an addition that was not present initially.

To enhance the efficiency of printing and enable automated transportation, the Israel Pound Series D (Dalet) was introduced and circulated between 1975-1978, featuring banknotes with a uniform width of 76 mm. The inaugural note in this series was the 500 Lira (Pound). Continuing the tradition, portraits of renowned Zionist leaders and statesmen adorned these banknotes, with a thematic focus on the unification of Jerusalem. Each banknote’s reverse side showcased a different gate of the old city of Jerusalem, earning the series the title of the ‘Gate Series.’ Some figures and gates from this series persisted through the subsequent two series, with alterations as the Israeli currency transitioned from the Lira to the Shekel.

The 5 Lira (Pound) featured the portrait of Zionist Woman Leader and founder of the Hadassah women, Henrietta Szold, against the backdrop of the Hadassah hospital on Mount Scopus. Szold marked the first woman to appear on an Israeli banknote, and the reverse side depicted a picture of Lions Gate. The 10 Lira (Pound) displayed the portrait of Jewish philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore with the Mishkenot Sha’ananim neighborhood and its iconic windmill in the background, accompanied by a picture of Jaffa Gate on the reverse side, narrating the exodus of Jews from the old city of Jerusalem. The 50 Lira (Pound) again featured President Chaim Weizmann, with the Wix Library building at the Weizmann Institute in the background, and a picture of the northern gate of the Old City of Jerusalem, Shechem Gate (Damascus Gate), on the reverse side. The 100 Lira (Pound) once more displayed the portrait of Theodor Herzl, this time with the entrance to Mount Herzl in the background, and the Zion Gate featured on the reverse side. The 500 Lira (Pound) portrayed the first Prime Minister of the State of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, against the backdrop of the library building at the Ben-Gurion Heritage Center at Sde Boker and the Tsin Valley landscape. The reverse side showcased the Eastern Gate of the Old City of Jerusalem, Sha’ar HaRachamim, also known as the Gate of Mercy or the Golden Gate, designed in desert colors.

While the background choice for Ben-Gurion’s portrait might initially seem surprising, it underscored his dream for the future of the Negev, offering a reflection on the fulfillment of this dream and a call to action.

The Gate series played a pivotal role in Israeli society, departing significantly from previous series. While earlier banknotes featured representations of Jerusalem, often depicting sites in West Jerusalem, this series emerged following the 1967 Six-Day War and the subsequent unification of Jerusalem. The unification garnered widespread admiration across Israeli society, transforming the city from a modern capital into a dual symbol of contemporary sovereignty and national-religious aspiration.

The deliberate choice to depict the gates of the Old City of Jerusalem on these banknotes made a profound political statement, articulating the emerging territorial ideology. This move elevated the new territorial vision from a political concept to a commonplace expression of nationalism, seamlessly integrating it into daily life through the currency. The banknotes effectively bridged the gap between the decision to incorporate the eastern parts of the city into the municipal area of Jerusalem immediately after the war and the formal enactment of the Basic Law: Jerusalem, the Capital of Israel, in 1980.

On June 4, 1969, the Knesset enacted a law stipulating that the currency unit would be the “shekel.” The implementation of this law was deferred to a date recommended by the Governor of the Bank of Israel. In November 1977, the government and the Bank of Israel deemed the conditions suitable for enacting the law. In May 1978, Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Finance Minister Simcha Ehrlich approved the governor’s proposal to create a new series where the currency would be the “shekel,” and its values would be obtained by eliminating the zero value of the pounds.

The banknotes were designed in the format of the D (Dalet) series, maintaining the same colors, size, and portraits, with the aim of facilitating public adaptation to the new values. The declaration of the shekel as legal tender occurred under emergency regulations on Friday, February 22, 1980, and the first banknotes entered circulation on Sunday, February 24, 1980. This series marked the largest issuance in the country’s history. Initially comprising four denominations (1, 5, 10, 50 shekels), and in response to rising inflation from 1981 to 1985, an additional five denominations were successively introduced—100 shekels, 500 shekels, 1,000 shekels, 5,000 shekels, and 10,000 NIS. The banknotes, starting from 500 shekels, were distinguished by unique colors and maintained a uniform size of 138 x 76 mm, resulting in significant cost savings in production expenses.

The design of the 1 Shekel bill mirrored the artwork of the preceding 10 Lira (Pound) Sir Moses Montefiore bill. Similarly, the 5 Shekel bill adopted the design of the previous 50 Lira (Pound) President Chaim Weizmann bill. The 10 Shekel bill replicated the artwork of the earlier 100 Lira (Pound) Theodor Herzl bill, while the 50 Shekel bill bore resemblance to the previous 500 Lira (Pound) David Ben-Gurion bill. The remaining denominations featured entirely new designs.

The 100 Shekel banknote featured the portrait of Revisionist Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky. The bill showcased arches from Shuni Fort, the former Irgun’s training camp now transformed into Jabotinsky Park. On the reverse side, the bill displayed Shaar HaPrakhim (The Flower Gate), also known as Herod’s Gate, in the Old City of Jerusalem. This dedicated bill was only possible after the political shift in 1977, marking the rise of the Herut party led by Menachem Begin.

The 500 Shekel banknote presented the portrait of Baron Edmond James De Rothschild, also known as Hanadiv– the generous one, with a group of agricultural workers in the background. The reverse side featured a bunch of grapes, and minstrel names of the forty-four communities he supported in the Land of Israel. The red color of the bill reflected his name “Roth” (Red) and his connection to the wine industry.

The 1000 Shekel banknote, later redesigned as the 1 New Israeli Shekel (NIS) bill, depicted an imaginary figure symbolizing the great Jewish Scholar Rabbi Moses Ben Maimon, Maimonides. The background displayed text from his monumental work “Mishneh Torah” in his handwriting, with a graphical view of Tiberias and a stone Menorah from archaeological excavations. The bill was distinguished by its green color.

The 10,000 Shekel banknote, also redesigned as the 10 New Israeli Shekel (NIS) bill, showcased the portrait of Golda Meir, the fourth Prime Minister of Israel. The background included a stylized tree with intertwined branches, and a pattern of the Menorah and the words “Shalach Et Ami” – “Let My People Go.” The reverse side portrayed Golda Meir greeted by a crowd in Moscow during her time as the first Israeli Ambassador to the Soviet Union, with the words “Shalach Et Ami” in large and small letters. The distinct gold color paid homage to her name.

The 5,000 Shekel banknote, later transformed into the 5 New Israeli Shekel (NIS) bill, featured the portrait of Levi Eshkol, the third Prime Minister of Israel, against the backdrop of United Jerusalem. The reverse side depicted a pipe carrying water and arid soil, symbolizing Eshkol’s contributions to water-related projects (Such as the National Water Carrier). The blue color represented the significance of water.

On September 4, 1985, the new shekel currency (NIS), equivalent to 1,000 (old), was introduced, marking the inception of New Shekel Series A (Alef). The removal of three zeros aimed to streamline cash transactions and enhance compatibility with machines and computers, while retaining the name “shekel.” Series A (Alef) of the NIS maintained the tradition of honoring prominent figures in Jewish history. The 1, 5, and 10 NIS banknotes resembled the shekel series but with a reduction in the number of zeros. The 20, 50, 100, and 200 NIS banknotes featured distinct colors from the previous series for easy public identification.

The 20 Shekel banknote featured a portrait of Zionist leader and second Prime Minister of the State of Israel, Moshe Sharett, with a list of the seven books he wrote in minuscule letters. The background displayed the hosting of the Flag of Israel at the United Nations building in New York in 1949, where Sharett attended as the first foreign minister of Israel. The reverse side showcased the original building of the Hagymnasia Hivrit Herzliyah in Tel Aviv, attended by Sharett, and ‘Little Tel Aviv.’ The bill was distinguished by its distinct gray color.

The 50 Shekel banknote displayed a portrait of Nobel Prize Literature laureate Shmuel Yosef (S.Y.) Agnon on the front, with a skyline of Jerusalem and a Jewish town in Eastern Europe on the back. The names of 18 books by Agnon appeared in tiny letters, and the bill was characterized by a distinctive purple color.

The 100 Shekel banknote featured a portrait of Zionist leader and the second President of the State of Israel, Yitzhak Ben Zvi, along with the titles of nine of his books in tiny letters. Portraits representing various Edot, ethnic backgrounds of Jews in Israel adorned the bill. The reverse side depicted the view of the village Peki’in, explored and researched by Ben Zvi, along with a picture of its ancient synagogue, the carob tree, the cave, and an ancient Menorah. The bill was distinctively brown in color.

The 200 Shekel banknote portrayed the third President of the State of Israel, Zalman Shazar, alongside a Menorah shaped out of a chain of the DNA molecule symbolizing scientific development. The background featured the song “Compulsory Education Law” written by Natan Altermin in 1949. On the reverse side, an image of a girl leaning at her desk against a backdrop of Hebrew typefaces was displayed. The bill was distinguished by its distinct orange color.

In 1999, the Bank of Israel introduced the New Shekel Series B (Bet), featuring the same individuals as Series A of the New Shekel with updated designs. Notable modifications were made to enhance the aesthetic and narrative elements of the banknotes.

The 20 NIS bill, featuring Moshe Sharett, incorporated an excerpt from Sharett’s speech at the UN on the front. The back depicted people walking during a demonstration in early 1945, carrying a poster for the Jewish Fighting Unit, the Jewish Brigade, initiated by Sharett during his tenure at the Jewish Department of the Jewish Agency. An excerpt from Sharett’s speech after visiting the Brigade in Italy was included, and the background showcased a scout tower from Maoz Haim, dating back to the Tower and Stockade period.

The 50 NIS bill, featuring S.Y. Agnon, displayed Agnon in the background of his study and library, with an added excerpt from his Nobel Prize speech. The front also incorporated a reference to Titus in Agnon’s speech, commemorating the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. On the back, Agnon’s writing stand, pen, glasses, and a list of sixteen of his books were depicted. The background featured the view of the Temple Mount with the Dome of the Rock, the site of the two Jewish Temples.

The 100 NIS bill, featuring President Ben-Zvi, showcased an image of Ben-Zvi in his presidential house during his term on the front. An excerpt from Ben-Zvi’s speech at the first meeting of the Yemenite community at the president’s residence in 1953 was added. The back displayed the synagogue in Peki’in and its landscape, along with an excerpt from Ben-Zvi’s speech at his swearing-in ceremony.

The 200 NIS bill, featuring President Shazar, presented a picture of an elementary classroom behind Shazar. The classroom board displayed the words “Shalom Kita A” (Welcome First Grade). An excerpt from Shazar’s address in the Knesset on July 13, 1949, after the adoption of the compulsory education law. On the back, an image of a typical alley in the city of Safed and the Aboab Synagogue was featured, along with a text from Shazar’s essay “Tzofayek Safet,” first published in 1950.

In 2014, the Bank of Israel introduced the current banknotes, the New Israel Shekel Series C (Gimel), featuring prominent Hebrew poets whose lives, creations, and actions are interwoven with the narrative of the rebirth of the people of Israel in their homeland. These banknotes exhibit an advanced level of security, innovation, and accessibility, incorporating various advanced security features against counterfeiting and dedicated signs for the benefit of the blind and visually impaired. Unlike the font used in previous series, which was deeply connected to the history and heritage of Hebrew script, the current series employs a cleaner, simpler, and more modern font.

The 20 NIS banknote pays homage to the poet Rachel Bluwstein, known as Rachel. The front features her portrait against the backdrop of palm tree branches, accompanied by a micro-lettering excerpt from her poem “Kinneret.” The reverse side depicts the landscape of the shores of Lake Kinneret, inspired by Rachel’s poem “Kinneret” and an excerpt from “Perhaps it Never Happened…”: “O my Kinneret, Were you, Or was I dreaming?”

The 50 NIS banknote is dedicated to the poet Shaul Tchernichovsky. His portrait is showcased on the front against the backdrop of a citrus tree and its fruits, inspired by the line “Smell of spring citrus groves” from his poem “Hoy Artzi Moladeti” -” Oh my country my homeland.” The back features a Corinthian style capital, representing Tchernichovsky’s interest in classical Greek works, along with the excerpt “for I shall still believe in both Men and his spirit, fierce spirit” from Tchernichovsky’s poem “Ani Ma’amin” – “I Believe.”

The 100 NIS banknote honors the poet Leah Goldberg. Her portrait on the front is set against the background of almond tree flowers, inspired by her poem “In the Land of my Love the Almond Tree is Blooming.” The back showcases a group of does, inspired by her poem “What do the Does Do?” along with the title of her first children’s book and an excerpt from the poem “White Days, As long As the Summer Rays of the Sun.”

The 200 NIS banknote is dedicated to the poet Natan Altermat. The front features his portrait against a background of fallen leaves, accompanied by miniature script words from his poem “Pgisha Lein Ketz” – “Eternal Meeting.” The reverse side displays moonlit flora and a verse from Alterm’s poem “Shir Boker” – “Morning Song”: “We love you our motherland, joyously, with our song and with our labor.”

This current banknote series is notable for being the first to exclude statesmen or politicians. Remarkably, it breaks away from the trend of featuring predominantly male figures, as it was designed by Osnat Eshel, the first female designer of Israeli banknotes, and signed by Prof. Karnit Flug, the first female Governor of the Bank of Israel. This series proudly exhibits a balanced representation, with 50% of the designs featuring women (2 out of 4). While acknowledging that Israel has not achieved complete gender equality, this development signals a positive shift and may be viewed as a testament to ongoing efforts in that direction.

However, criticism has been voiced regarding the exclusive representation of Ashkenazi poets in this series, raising concerns about the lack of inclusion of Mizrahi poets, intellectuals, or cultural figures. It highlights the need for broader representation to reflect the diverse cultural fabric of Israeli society.

Over the past 75 years, the design of Israeli banknotes has evolved significantly. The committees and designers responsible for shaping the appearance of the currency aimed not only to portray individuals but also sought to encapsulate the essence of the state. Beyond capturing the spirit of different eras, they assumed the responsibility of influencing Israeli society through the currency in circulation. As Israeli society undergoes constant transformation, it is likely that future designs will continue to reflect these changes.

The advent of new payment methods, such as checks, traveler’s checks, credit cards, and bank transfers, has diminished the need for physical currency. Today, digital wallets, online transfer applications, and bank transfers are shaping the way transactions occur. While the currency may not fully represent the economic prosperity of the state, it serves as a testament to the richness of Israel’s people and culture. For visitors to Israel, obtaining some cash not only facilitates interactions with local merchants but also provides a genuine experience of Israeli life.

[i] Mordecai Naor, ‘The Birth of Israeli Currency’, in 1948 – Stories and Events, Israel, 2018. Pp 347-351. [Hebrew].

מרדכי נאור, ‘הולדת הכסף הישראלי’, בתוך תש”ח- 70 סיפורים ופרשיות, 2018, עמ’ 347-351.

[ii] Itamar Atzmon, Segula, May 2011 [Hebrew].

איתמר עצמון, מטביעים חותם, סגולה, גיליון 12, אייר תשע”א (מאי 2011).

[iii] Archaeologist Yigal Yadin at the first meeting of the committee members discussing the pound series b “If we accept the assumption that a strong bill is the carte de visite of the state […] one side can represent the past of the people of Israel, the same past from which we grew, from which we draw our forces, and on the other hand, the other side can represent the present and future Israel aspires to it.”

In Naama Shefi and Anat First, The City Connected Together: A Look Through the Banknotes, Studies in the Restoration of Israel (Dovrat Topic, Vol. 11): Israel 67-777, pp. 387-406. [In Hebrew]

נעמה שפי וענת פירסט, העיר שחוברה לה יחדיו: מבט דרך שטרי הכסף, עיונים בתקומת ישראל (דברת נושא, כרך 11): ישראל 67-777, עמ’ 387-406.